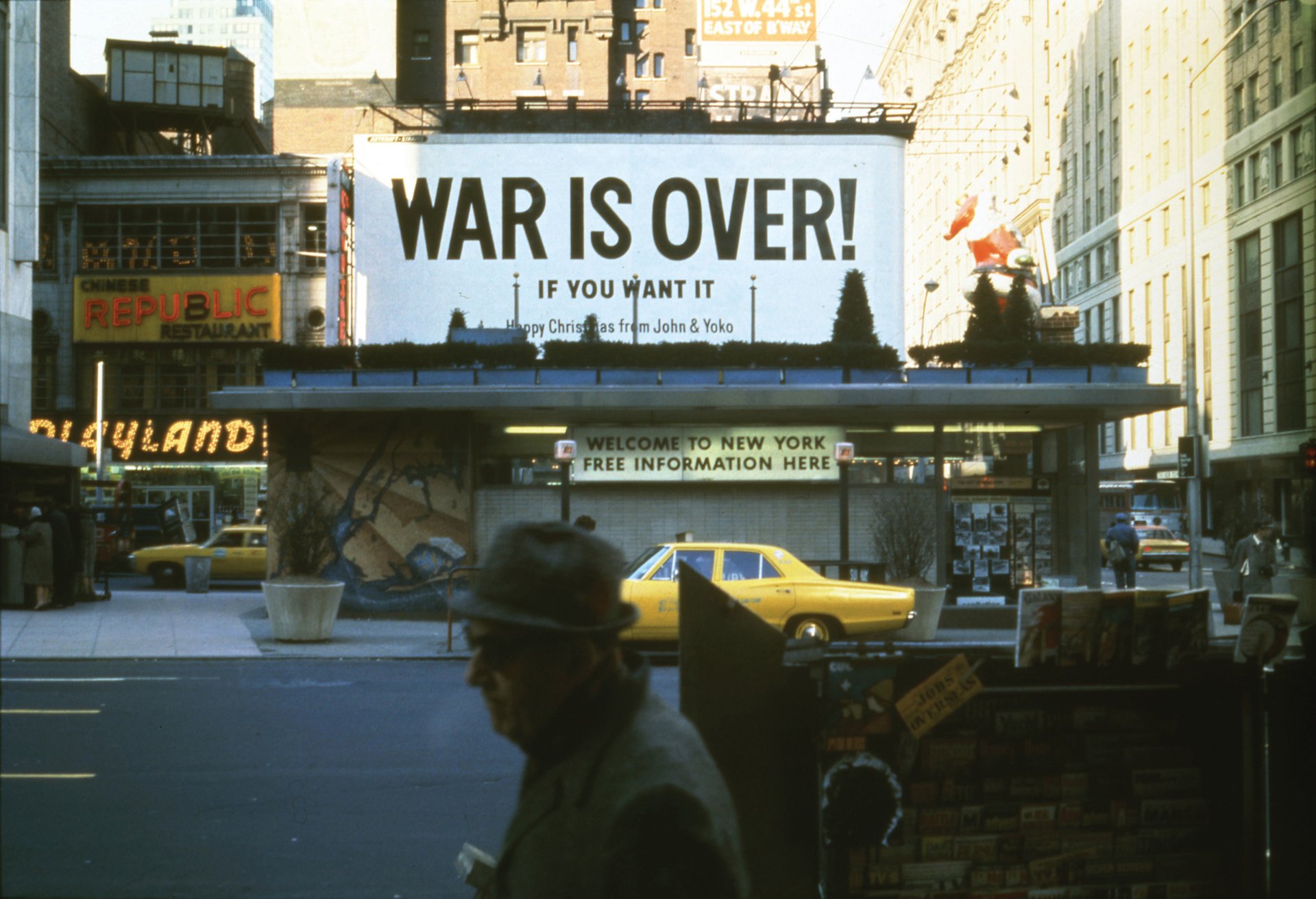

Yoko Ono, who turned 83 in February, has made her presence felt for more than 50 years in a variety of incarnations—artist, musician, singer, anti-fracking activist and tabloid newspaper staple in the guise of John Lennon’s eccentric widow. However, her conceptual innovations in music, sculpture, photography and film, which fuelled the New York avant-garde in the 1960s, arguably prefigure the work of numerous contemporary artists.

Ono seems more prolific than ever, with her practice and philosophy under scrutiny in a stream of recent shows and retrospectives, including Half-A-Wind at the Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, in 2013. The organisers of the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao leg of the retrospective, in 2014, described her artistic ideas as being, in many cases, “poetic, absurd and utopian”, yet noted that “others are specific and practical”.

Ad-libbing is important. I know my intentions but do not know what is going to happen

The artist’s first solo show in Beijing, now on view at the Faurschou Foundation (until 3 July), attracted nearly 10,000 visitors during its opening week last November. Her debut institutional solo show in France opened at the Musée d’Art Contemporain in Lyons last month. Lumière de l’Aube (until 10 July) features 100 works, from her illustrated poems of 1952 to new versions of key installations such as Morning Beams (1997/2013).

The Art Newspaper: Thierry Raspail, the co-curator of the Lyons exhibition, says that your art is “utterly relevant”.

Yoko Ono: Well, thank you—but anything and everything is relevant! What I really think is that we’re all connected and every one of us has a position to take in this world. I think that there is no difference between the old and young. That’s why I don’t like the idea that people kill each other; it’s a waste of time, a waste of life. I want to elaborate: we talk about male society and freedom, [but] the actual reality is that the world is made of men and women. If this world does not use female power, it’s bad for the world of male society.

That brings to mind your 1972 thesis Feminisation of Society.

Well, we [women] were kind of ignored.

Sound and performance are an integral part of your canon. Will you create a playlist for the Lyons show?

No, I’m not creating a playlist for the show. I know vaguely what I’m going to do. When I say I know, theoretically in a performance-art piece, it’s about ad-lib. Ad-libbing is very important. I know my intentions but do not know what is going to happen. When I started doing that [performance art], there was no word for it.

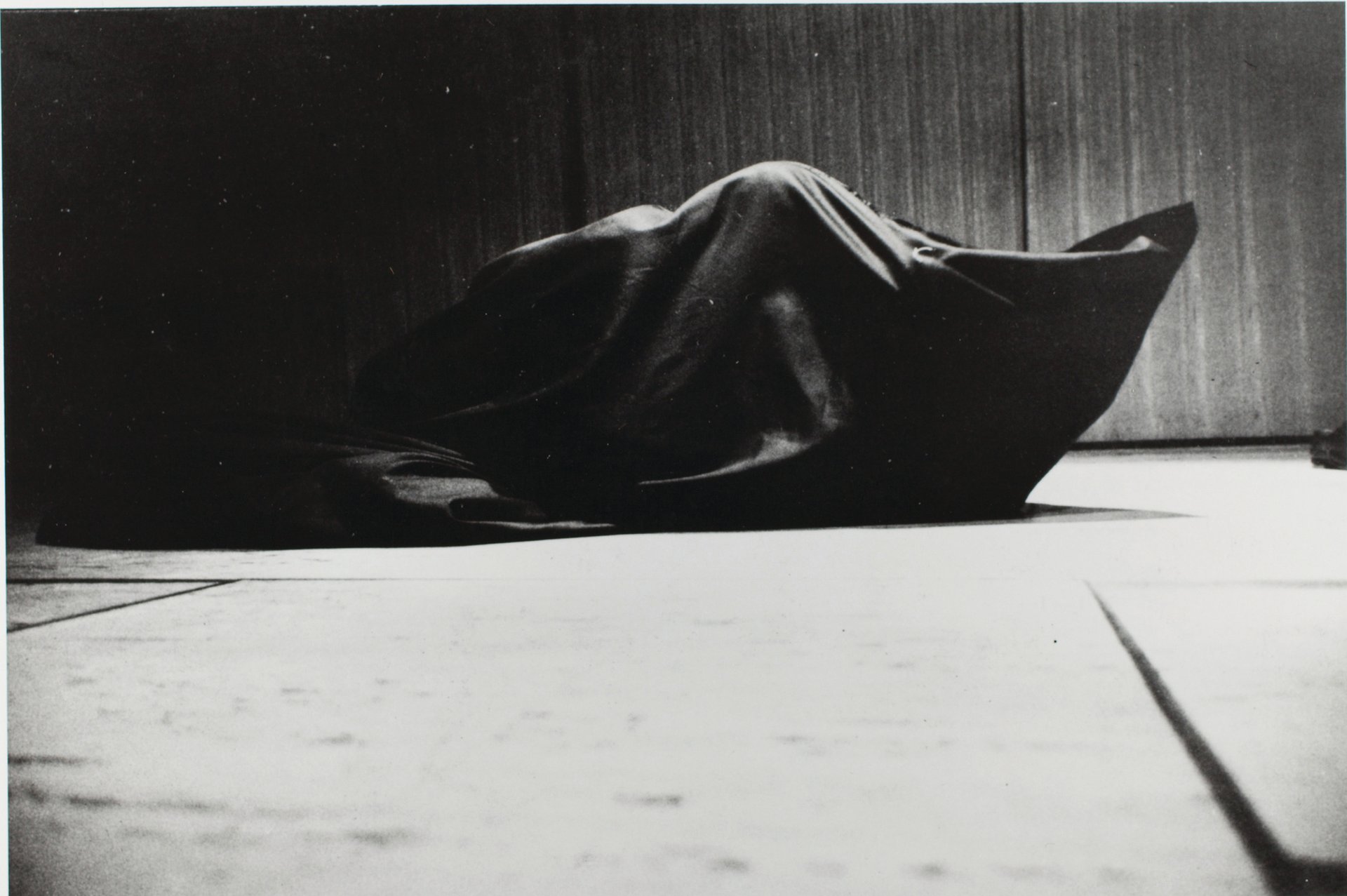

I have entitled the show Lumière de l’Aube [light of dawn] because it is about a start, you see; the start of a sunrise. There is also a piece called Lumière Room, which is the one I always wanted to do but couldn’t for many reasons. It’s a kind of room; the walls are not transparent but like a [type of] paper. People cannot really see inside, but can sense the shadows. When someone enters the piece, they get into a bag. There is intense light coming from all four sides: east, west, north and south. The light goes through a cycle of 365 days—this happens over two hours. You’re in the bag; you’re bathed in light.

The world is very fast now because of the computer age, but, philosophically speaking, whether we go through 365 days in a minute or 100 years, it all depends on our brains.

So are you reworking an earlier concept?

It’s very similar to [an untitled] piece I did in 1965 or 1966. It was not called Lumière, as it was then at a very primitive stage. What I discovered then, I did not relate to science. But around a year ago, US scientists started to talk about the intense light given to the brain in cycles, and how this changes the brain and the world. I thought, “What did I do?” But I did not know this would be a reality. I thought of it as a poetic reality.

You’ve often drawn on science. Are you a fan of computers and technology?

I like computers. You know why? Because I’m always interested in creating new forms in music, or in art, poetry, film. I think that if you cannot create new forms, you’ll die. What I want to do is keep on creating and, through that, have life. When you improvise, you’re going somewhere you don’t know. That’s how we progress, not by sticking to something. It’s a way of life, not death.

Grapefruit, your self-published 1964 book of more than 150 “instructions for pieces”, reads like a series of tweets.

I think this is a new form of art. Each one I did, I hoped they were slightly different [to the ones] before. Therefore, it’s a new form. I think of social media as a new form of art. The Instruction Paintings [Ono’s series of typed instructions, dating from 1961] created a new development, almost by giving you a whisper. For me, it seemed like a new form.

But religion also plays a part. When you did Cut Piece [see key works, opposite], you said it was a Buddhist “act of giving”.

It was not that scary when I started doing it, as you’re inside yourself. You can say it’s a Buddhist influence or a Christian influence, or whatever, but all that is just words.

Have you become more mischievous over time?

Well, life is playful. It’s like two sides of the coin; it’s always playful and serious, serious and playful.

That’s difficult to achieve in art.

No, you don’t achieve it. Leave me to find out what life is. Don’t think: “Please make it serious, please make it playful.” You’ll never succeed.

Do you often think about how you have survived, especially as a child, living through the Second World War in Japan?

That was a very difficult time. I kept drawing every day and almost every night. What came out of it was something I didn’t realise—not one thing [is the same]; each thing is different. Where did that shape come from? It helped a lot.

Do you think people take you seriously?

I feel much stronger now, stronger in my body. The other day, I thought, “This is the secret: take a cold bath every day.” It has to be very cold.

Are you always this optimistic?

We’re all pebble people [Ono’s 2010 essay Pebble People was written to mark Earth Day]. When you’re by the ocean, throw one or two stones. Two scientists who were researching waves discovered that anything dropped in the ocean goes around the whole ocean. When you think about that, we have the power to circulate the whole world. So the thing is, each one of us is important.

Finally, given that you’re showing in France, do you have a favourite French artist?

Before the end of “peinture-peinture” [pure painting], Impressionism was at its peak in France. Then Picasso and Braque brought a small alien element into art. It is for this reason that my heart beats for Cubism.