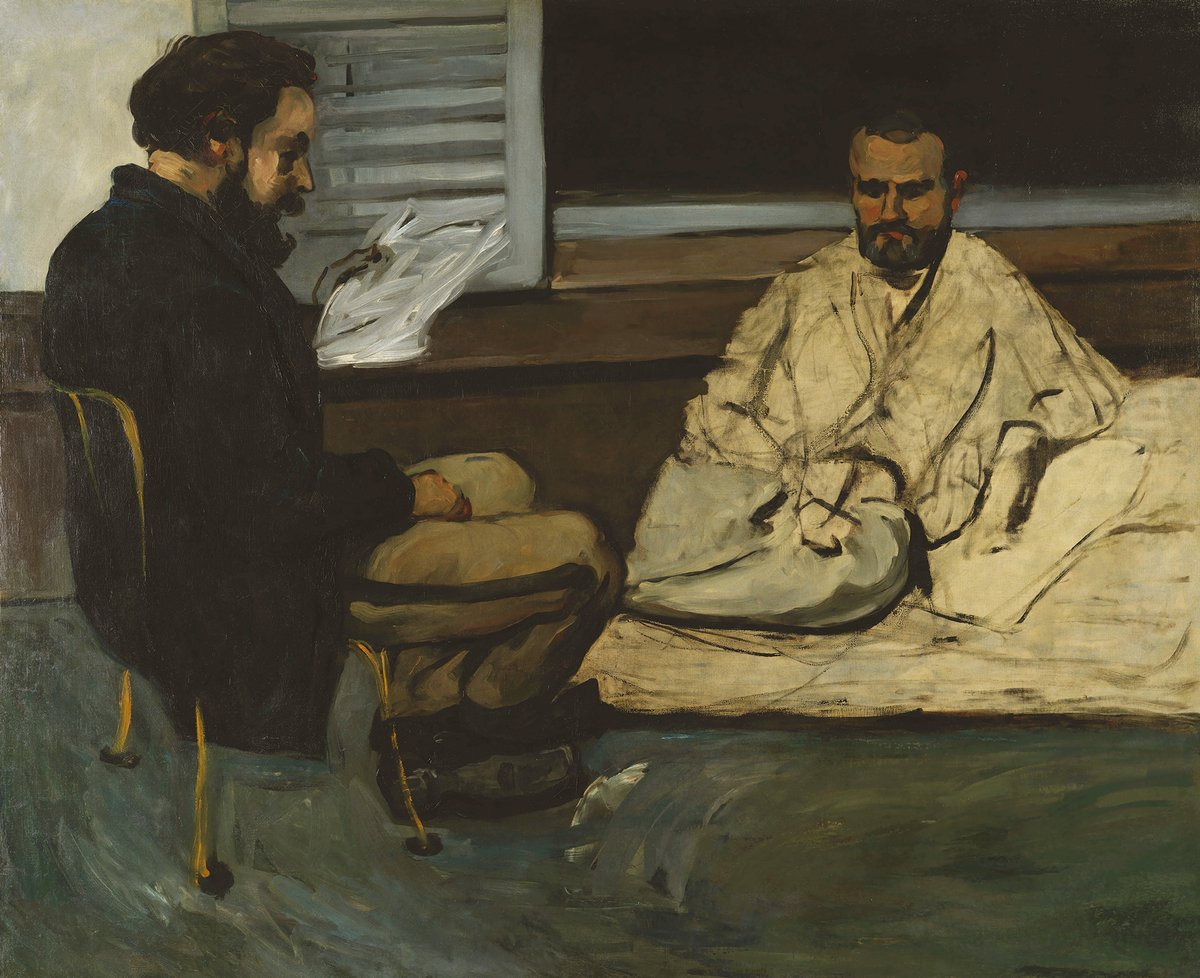

Cézanne Portraits, which opened this week at the National Portrait Gallery (until 11 February 2018), is a rare opportunity to see the development of Cézanne’s painting style across one of his more overlooked painting genres, portraiture. Although at times he seems to be grappling with his medium, there is a sense that he gets a real kick out of it too. The different styles range from the refined brushwork of Portrait of the artist’s son (1883) and the wispy yellow chair leg in the unfinished Paul Alexis Reading a Manuscript to Emile Zola (1869-70), to the thick impasto applied with a palette-knife in a series of his uncle Dominique (1866–67). Cézanne described the latter technique as the “couillarde” (from coquilles—to have balls) method. The exhibition includes more than 50 works, many of which have not been exhibited in the UK before, such as the artist’s bowler hat self-portraits and two paintings of his wife, Hortense Fiquet.

It is a cruel fact that illustrators are often widely loved at the expense of critical approval as “serious” artists. That is arguably true of Finnish artist and author Tove Jansson (1914-2001), known the world over as creator of the Moomin books for children. But, in her first UK retrospective, Dulwich Picture Gallery (until 28 January 2018) shows Jansson’s talents extended beyond those whimsical, snouted characters with a display of 150 paintings, drawings and graphic illustrations rarely seen outside Finland. From the Surrealist-influenced paintings of the 1930s and satirical anti-war cartoons, to 1960s experiments with abstraction (plus a healthy dose of Moomin sketches too), Jansson shows herself to be politicised and questioning rather than merely cosy.

Much influenced by Sigmund Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams, Alfred Kubin’s dense drawings of nightmarish visions are the epitome of fin-de-siècle torment. Known as the Austrian Goya, Kubin’s life was dogged by tragedy: after his mother died when he was ten years old, Kubin’s father immediately married her sister but she then died in childbirth the same year. Aged 19, Kubin tried to commit suicide on his mother’s grave and, in 1903, was again on the brink of suicide when his fiancé died suddenly. Richard Nagy has brought together 50 rarely seen works in Alfred Kubin: Munich 1898-1906 (until 3 November) that show the artist tapping into his “other side” with a disturbing lack of empathy, as primal desires and fears about sex and death play out unfettered.