A taster of our interview with Alex Farquharson David Clack

Alex Farquharson, the director of Tate Britain, is planning a complete rehang of the gallery, five years after the last major transformation of the displays in 2013. In an interview with The Art Newspaper, he outlines a new vision for the collection based on three “pillars”: art and society, history and the present, and Britain and the world.

The current Walk through British Art display, unveiled by his predecessor, Penelope Curtis, arranges over 500 works from five centuries by the year they were made (the date of each room is set in gold on the floor). Farquharson’s revamp, emphasising the social context of British art, will have a looser chronology and some thematic elements. It could be completed in 2020.

Farquharson, who joined Tate Britain from Nottingham Contemporary in 2015, also reacts to concern about the museum’s attendance. Tate Britain received 1.4 million visitors in 2016-17, compared to a record 6.4 million at Tate Modern (thanks to its new extension). Though the Tate Britain figure was boosted by the David Hockney blockbuster last spring, it falls well short of the National Portrait Gallery (1.9 million) and is not much more than the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich (1.3 million).

There is a possibility, however, that Tate Britain will join forces with Tate Modern, or another national museum, for a future mega-exhibition. Such a collaboration would be a “powerful statement”, Farquharson says.

The Art Newspaper: How has the Tate changed since the departure of Nicholas Serota and the arrival of Maria Balshaw as overall director?

Alex Farquharson: Nick was a great director. It is still early days, but Maria has a different style. She communicates inclusively and openly. She is very committed to diversity—within the organisation, in programme content and in how we engage with audiences.

You have developed three new “pillars” that will guide Tate Britain in the future.

Tate Britain has an exciting role in presenting art in a societal context, both past and present, so it is a question of the stories that we tell. I have set out three pillars that inform our curatorial choices and how we communicate them. These are a trio of relationships: art and society, history and the present, and Britain and the world.

What impact will this have on exhibitions and the collection?

It is already a filter through which we make exhibition decisions. One of my earliest decisions was to say yes to Queer British Art 1861-1967, which closed in October. The demographics of our visitors were very different from usual—the average age was 35 and 55% self-identified as LGBT.

But the three pillars should have a more explicit impact on collection displays. The present display is chronological, but we will look to thematise it. The displays will still present a movement through time, but there will be overlapping chronologies between different rooms, particularly as the collection gets larger from the 18th century onwards. We want to contextualise the collection, especially with regard to art’s relationship with culture and society. Art can serve as a lens through which to look at ourselves and the world.

Will there be a full rehang?

Yes. We now have a set of ideas we are thinking about, but we don’t yet have a date for the rehang. The work would be done at some point in the next few years and would take some months to complete, shutting a few rooms at a time while we install.

To what extent should Tate Britain be international in its scope?

British artists are, and always have been, part of the international story. In the past we have thought more about Europe and North America, but I want to think intercontinentally. The Caribbean, for example, will be a reference point in the coming years. What we do and how we do it should aim to reflect the communities that we serve.

Tate Modern’s visitor figures have soared ahead over the years, whereas Tate Britain’s have been fairly stagnant. Are you concerned?

[The calendar year] 2017 will have been a bumper year, with around 1.7 million visitors. This is partly due to the spectacular success of the David Hockney show last spring. With 478,000 visitors, it has been the most popular exhibition on a living artist in the Tate’s entire history [it is now at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, until 25 February]. I believe that we should normally be in a position to exceed 1.5 million a year.

Hockney demonstrates how important exhibitions are, but surely not enough people are coming to see the collection?

Two-thirds of our audience come for the permanent collection only. Yet our marketing focus tends to be on temporary exhibitions. So we are thinking about how to tell the story of the collection around the year. That’s more of a challenge, because you don’t have beginning and end points.

What about the make-up of your audience?

We offer a wonderful reflective experience for individual visitors, but we would like more people to visit in small groups and couples. We particularly want to engage with younger audiences, many of whom seek a more social and participatory experience in museums. That involves activating our spaces beyond the galleries themselves and further developing the digital. I want to enliven the façades of the building and make more use of the garden at the front in the summer—perhaps for participatory artworks, and as a space for children and the local community.

Would the Tate consider holding a single exhibition across its two London venues?

That would be interesting. We might also consider an exhibition at Tate Britain and another national museum. It would have to be relevant to the two sites and be one that would require a very large space that neither could offer alone. We would need to look at the commercial arithmetic, because you would probably need to charge at both sites. But assuming there is a solution, it would be a powerful statement.

Will you be a hands-on curator for any forthcoming shows?

I will be co-curating a show in 2020. But I see my role more like an editor of a newspaper, looking at the overall picture, and supporting and advising curators.

What do you enjoy most about your job?

I am passionate about bringing art to as wide an audience as possible. The cultural influence that Tate has is exciting, while also a great responsibility. Tate has a huge influence beyond the art-interested audience—it really matters to Britain. And I get great pleasure from dialogue with curatorial colleagues and artists.

Director’s pick

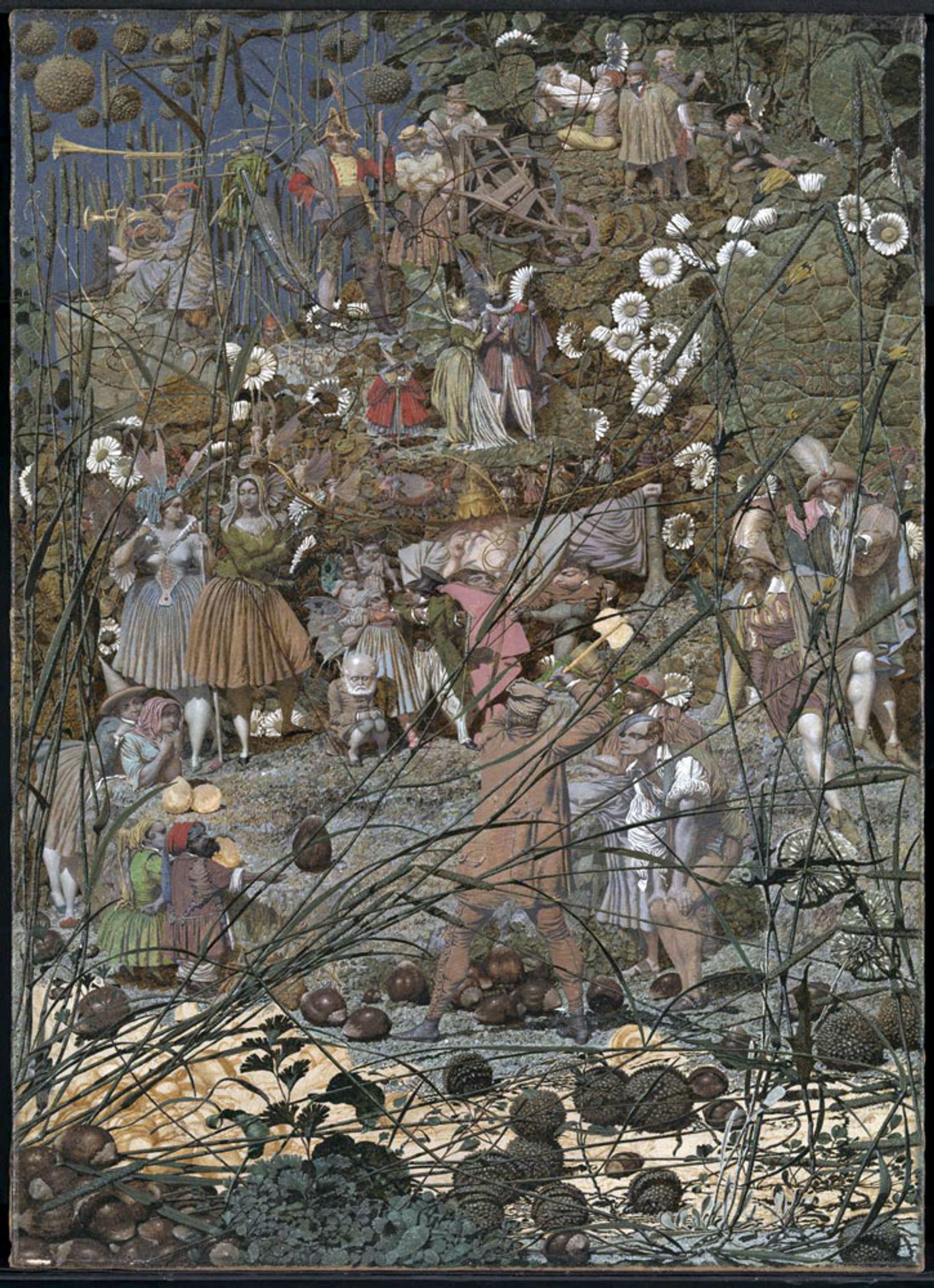

Richard Dadd's The Fairy Feller's Master-Stroke (1855-64) Tate

When asked to pick a favourite among more than 70,000 works in the Tate collection, Alex Farquharson, a contemporary art specialist, made a surprising choice. Richard Dadd’s The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (1855-64) was painted at Bethlem Hospital (Bedlam), where the Victorian artist was committed as a “criminal lunatic” after he murdered his father. “If one needs to think in an out-of-the-box way, this painting is a great reminder to do so,” Farquharson says. The painting is currently on view in Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries, selected by the artist Rachel Whiteread in connection with her major retrospective (until 21 January).