Decades ago, Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates said: “The internet is becoming the town square for the global village of tomorrow.” That town square now has a Starbucks on every corner, probably next to a Theory or Apple store and, as of March, maybe a few dozen high-end art galleries.

As the digital existence and experience of art proliferates at rapid speed under lockdown, so too does the commercialisation of the virtual art landscape. Like central districts in any city like London’s Mayfair or New York’s Chelsea or Soho, where luxury retail and global franchises have displaced independent businesses and storied artist-run spaces, is it possible that a similar stratification and homogenisation of culture is underway as major galleries race to open their virtual storefronts and viewing rooms while coronavirus (Covid-19) keeps their physical ones shut?

“Everything is so flat—except for the [infection rate] curve,” Magda Sawon says of the online art landscape that has developed amid the global pandemic. The New York-based dealer opened Postmasters gallery in 1984 to showcase emerging artists, especially those working in new media. A number of the artists she represents have started their careers by working exclusively online, like Eva and Franco Mattes, who also make work under the moniker of their website, 0100101110101101.org, or Rafaël Rozendaal, one of the first artists to sell websites as works of art.

“I was preaching day and night of the internet being just another tool or medium [for artists]”, Sawon says, likening binary code to paint on canvas. “So many people didn’t see art on a screen as legitimate, though.”

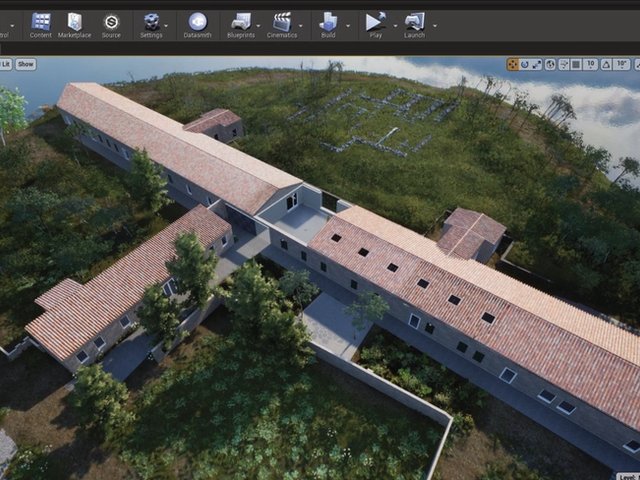

Now, in the eye of the Covid-19 storm, all art is screen-based. Consider the launch of Hauser & Wirth’s first-ever virtual reality (VR) exhibition, Beside Itself, which debuted on 30 April. Rendered with technology created in-house called HWVR, the show offers a preview of the gallery’s new Menorca outpost. With Google Cardboard glasses affixed to better their view, visitors can take in not only the architecture, but a monumental Louise Bourgeois spider and a Lawrence Weiner mural—a new work created specifically for the exhibition—upon “entering” the space. Both works, even the Bourgeois, which pre-existed the show, are rendered pixel by pixel with HWVR, meaning they are digitally native, not predicated on anything IRL other than an idea.

A virtual preview of Hauser & Wirth's Menorca space, complete with a Louise Bourgeois spider sculpture. Hauser & Wirth via Vimeo

Hauser & Wirth has nearly a dozen outposts around the world and Marc Payot, the gallery’s president, says development of HWVR began around two years ago to increase the efficiency of planning shows at its different locations. “We don’t think about this as a replacement for a real show,” he says of the gallery’s virtual exhibition. “This is just a way for us to reach new clients.”

Just a website?

Despite a rise in online sales, the art world has insisted art must truly be experienced in real life, not virtually. Sawon may have been a pioneer of the online selling exhibition: she staged her first all-digital show, Can you Digit?, in 1996, featuring around 40 works, many by West Coast artists and designers with close ties to Silicon Valley. Although staged in the physical gallery space, the intention of the show was to reveal how art, design and technology have always grown together and all works were hosted on screens.

“The viewing room concept has existed since the advent of the website,” Sawon says. The current glut of virtual art-viewing experiences is less of a legitimisation of art's connection to technology, however, she explains: “It’s all just panicked marketing and promotion. The volume of ‘new’ online features is so overwhelming it borders on abusive.”

Ultimately, the current surge to sell online belatedly reflects the spread of online retailing in general, which has grown hand over foot over the last two decades since Amazon entered the arena. Before Covid-19 became the pandemic that broke the camel's back, buying art on the internet had become far more conventional, even if not always preferable, with online marketplaces like Artsy and auction houses like the now-bankrupt Paddle8 popping up in the spirit of making art more widely and easily available by reaching new clients and audiences. Major auction houses, too, took to hosting regular online sales and blue-chip galleries routinely sold work “off a jpeg”, an ubiquitous but morally controversial business practice that some say is cheapening— for the aura of the artwork if not the artwork itself.

But just because you can put a work of art online does not mean you should. “I don’t blame anyone for feeling like they need to programme an online space purely for economic reasons right now,” says Aria Dean, an artist as well as the editor and curator of Rhizome, an organisation affiliated with New York’s New Museum dedicated to archiving and presenting digital art and culture. “But what we’re seeing a lot of is the same as setting up a painting on an easel in the middle of a desert.”

Of the current virtual real estate grab underway in the art world, Dean says: “Like moving art spaces into any location historically, it should be a conscious choice that benefits the ecosystem.”

Korakrit Arunanondchai's History painting (frame) is offered by Carlos / Ishikawa gallery on David Zwirner's Platform:London. © Korakrit Arunanondchai. Courtesy the artist and Carlos / Ishikawa, London

She points to David Zwirner’s Platform initiative, a collaborative online exhibition that showcases works by select smaller galleries on the mega dealer’s established online platform. First debuted in March “in” New York, with London and Los Angeles editions quickly following, the seemingly communal enterprise “is shifting the environment—in a certain way”, Dean surmises.

“This type of open-source collaboration and resource-sharing will be key for the health of the art-world ecosystem at this moment,” says Elena Soboleva, Zwirner’s director of online sales, adding that “the gallery world is interconnected, and a rising tide lifts all ships”.

Zwirner was one of the first blue-chip dealers to stake out a substantial online plot when he launched his viewing rooms in 2017, positioning it as discreet space with its own programming, akin to as if the dealer had opened an additional space in a new city.

“It feels like a start-up—everything is iterating and moving quickly and we are growing and scaling up our projects and launching new products for the gallery,” says Soboleva, who joined in 2018. “Given how many potential collectors there are who are outside major capitals, and not served by any of our physical locations, it feels like a world of opportunity for galleries of every size.”

First phase of many

A progressive narrative of egalitarianism has long accompanied internet culture. “The big gallery doesn’t have an advantage in this space except that maybe it has bigger artists,” Payot says, adding that a recent online-only sale of drawings by Rashid Johnson sold out almost immediately.

While the opportunity to use the internet in innovative ways to the benefit of their artists is available to any gallery with WiFi, as bigger and more established move into the space, their visibility may decrease. Bigger galleries, then, can choose who they want their neighbours to be, creating a kind of digital displacement. The risk for dealers, like any venerable mom-and-pop shop in an area undergoing rapid commercial development, is displacement by larger, wealthier entities vying for the space. The internet, of course, is not bound by physical parameters—but it is limited by a user’s attention span.

Everybody can put stuff on the internets. I worry that in online art presentations fancy delivery will override content. So much irrelevant bling out there to literally and metaphorically "navigate". Another wealth gap. Collectors should look beyond bells and whistles.

— magdasawon (@magdasawon) April 15, 2020

"The internet has always been tied to geopolitics and consumption," Dean explains. This is just the first phase of many on a more local scale—"a kind of curatorial selection era”, she says of the gallery migration to online venues right now, even when it is by necessity and even when it comes to something as seemingly well-intentioned as Zwirner’s Platform series. “It’s ultimately closing the ranks.”

As the volume of online exhibitions grows, Sawon fears that not only will smaller galleries get overlooked in the same way they have been pushed out of art districts like Chelsea, true innovation in the realm of digital art will be lost in favour of the latest virtual or augmented reality feature.

“It's all just clogging people's attention bandwidth. This 360-degree navigation its bullshit, that kind of technology was already there," she says of the increasingly sophisticated viewing rooms being unveiled day after day. "This is a who’s-dick-is-bigger-fight, it has nothing to do with the art."

Yet Sawon maintains that she is optimistic. “I don’t have this vision that we are in the end game of culture. This crisis is also bringing radicalisation; there will be new ideas—no one needs to look to the mega galleries as gods,” she says. “Everyone should look to what they can do within their means.”