Luchita Hurtado was deeply moved when she first encountered a photograph of Earth as a tiny blue object seen from outer space: presumably the extraordinary Pale Blue Spot —a tiny, feint sphere, caught against the void—taken from the edge of the solar system by the spacecraft Voyager in 1990 before it passed forever into interstellar space.

“I realised how interconnected we all are,” she told The Art Newspaper earlier this year. “The Earth is my planet, and I’m involved with everybody in this world ... I care about what happens to our planet.” It was a moment, she said at the time of her one-woman show at the Serpentine Gallery in London in June 2019, that she realised, “We are all on this planet and we are all related, and our closest relative is a tree, because they breathe out and we breathe in.”

Nature, and the power of the senses, first led Hurtado to art. As a child she possessed an extraordinary sense of smell. She recalled—when interviewed for the Archives of American Art of the Smithsonian Institution in 1994 and 1995—being in the garden at home in Venezuela in the 1920s and detecting “this very pungent, extraordinary scent. I would follow it and I would see a butterfly breaking its cocoon.” She experienced "extraordinary feelings" for that emergent tropical butterfly, and the rich, colourful patterns on its wings remained a vivid memory. Painting, she said, became in time a necessity: “It was like breathing ... it was hard not to.”

And when, in Hurtado’s tenth decade, the range and quality of her work was revealed to the art world for the first time—at a group show at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles in 2018, and then at the Serpentine show last year—the Earth and nature were powerfully apparent. There were drawings of figures, half-tree, half-human; the I Am self-portraits, where the view is Earthwards, of feet, navel and breasts; surrealist "Body Landscapes" where the human figure assumes the form of mountains and sand dunes; human and plant forms examined as cross-sections broken down into organic, cellular patterns; and graphic pieces assembled around the words Air, Water, Earth and Fire. One of Hurtado's pictures, The Last Leaf of Rachel Carson—a seascape with the horizon formed by a leaf—is a homage to the marine biologist whose transformational book on the dangers of pesticide poisoning, Silent Spring (1962), gave rise to grass-roots ecology movements all over the world. Leaves, feathers and fruit appear frequently as symbols in Hurtado's work. “I am very sensual; I love smells and tastes. I love fruit, you see," she said. "Religion is full of fruit. And an apple means more than an apple!”

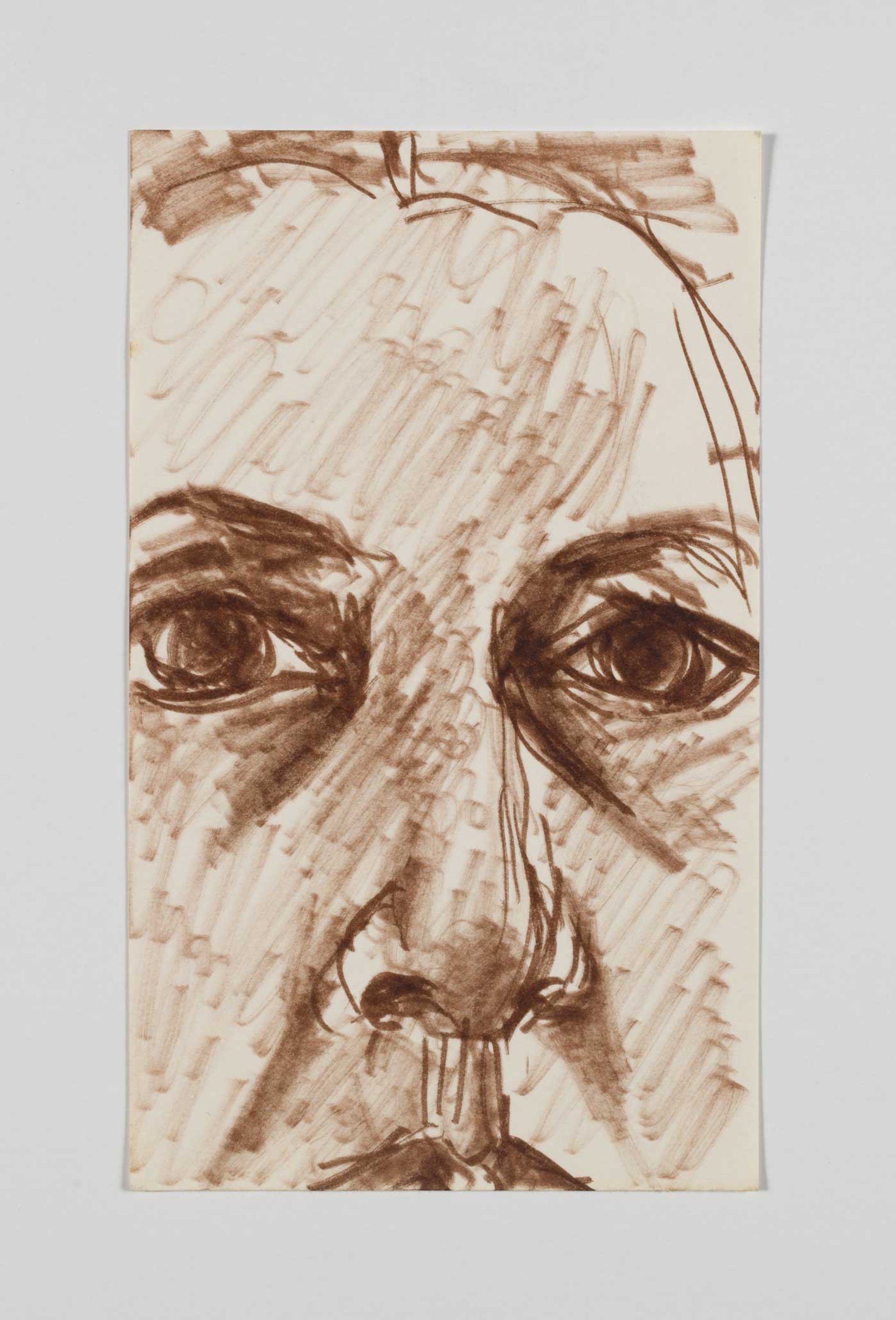

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, c1960s, ink on paper © Luchita Hurtado. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane

A house of women

She was born Luchita Garcia Rodriguez in Maiquetía, a coastal town west of Caracas, in 1920. At the age of eight she moved to New York City, to join her mother, her elder sister and her mother’s two sisters. Her father remained in Venezuela. It was a house of women; her mother worked as a seamstress. They lived way uptown but Luchita went to school way downtown, at Irving Washington High, in Greenwich Village. Her mother thought Luchita was studying sewing, but she was studying art. Her original dream had been to be an engineer, "to build bridges", despite her weak grasp of maths. Engineering and art were not, her mother thought, careers for women. But Luchita was determined to make her own mark. “I’ve always followed my needs,” she said in 2018, “my heart, my brain.” Being called Garcia Rodriguez, she said in 2012, was “like being called Smith Jones ... I decided that wasn’t right, and I chose my grandmother’s name on my mother’s side—Hurtado.”

As a teenager she volunteered at La Prensa, a Spanish-language newspaper in New York, where she met Daniel del Solar, a Chilean journalist at the Associated Press, a much older man, an intellectual who she saw then as a "very extraordinary spirit". They were married when she was 18 and led a peripatetic life. Del Solar was invited to the Dominican Republic by its dictator, Rafael Trujillo, to start a newspaper, working with an editor from Madrid. In Santo Domingo, Hurtado encountered the large diaspora of Europeans— writers, musicians, artists—who had been displaced by the rise of Nazi Germany. Del Solar proved insufficiently deferential to Trujillo and they moved back to New York City, where they lived downtown, in Christopher Street, with a period spent in Washington, DC, where Del Solar worked for Time magazine. Their first son, Daniel, was born in 1940, and a second, Pablo, two years later.

Through the 1940s, when she was still in her 20s, Hurtado, who was sociable and sympathetic and made friends easily with both men and women, came into contact with a wide array of fellow artists, among them the future stars of the New York School—including Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell, both of whom became valued friends—and the large numbers of European and Latin American expatriates she met in New York and later in Mexico and California.

I am very sensual; I love smells and tastes. I love fruit, you see. Religion is full of fruit. And an apple means more than an apple!Luchita Hurtado

At this time, the sculptor and designer Isamu Noguchi, whose sister, the dancer Ailes Gilmour, was lodging with Hurtado and Del Solar in New York, became a close friend and remained so, "like a brother", until his death in 1988. Hurtado also became friends with the Mexican artist Rufino Tamayo and his wife Olga, and with the American artist Ann Clark and her husband, the Chilean Surrealist Roberto Matta—who had been closely associated with Le Corbusier and André Breton in Paris in the late 1930s.

As a teenager, Hurtado had valued Robert Hale's art classes at the Art Students League of New York, but the first artist to have a sustained influence on her was Tamayo. In early 1941, when he was teaching at the Dalton School in New York City, and his wife was ill, Tamayo would come over to her house and, Hurtado remembered, "made some of his portraits of dogs in my kitchen [including Animals, 1941, in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York]. Or to pass the time we would play a game of figuring out how to make this colour—the colour on the wall, or the colour of a book. How do you make this green? And we would take out the paints and mix them. It helped me find my favourite colours and colour combinations."

From Motherwell to Mexico

One day Del Solar walked out on Hurtado and the children, pausing only to collect his books. She put Daniel and Pablo into school and found work in New York, painting murals for the windows of the department store Lord & Taylor and as a fashion illustrator for Condé Nast—to prepare her portfolio she studied what the magazines were doing and, with a typical sense of independence, “did the opposite”.

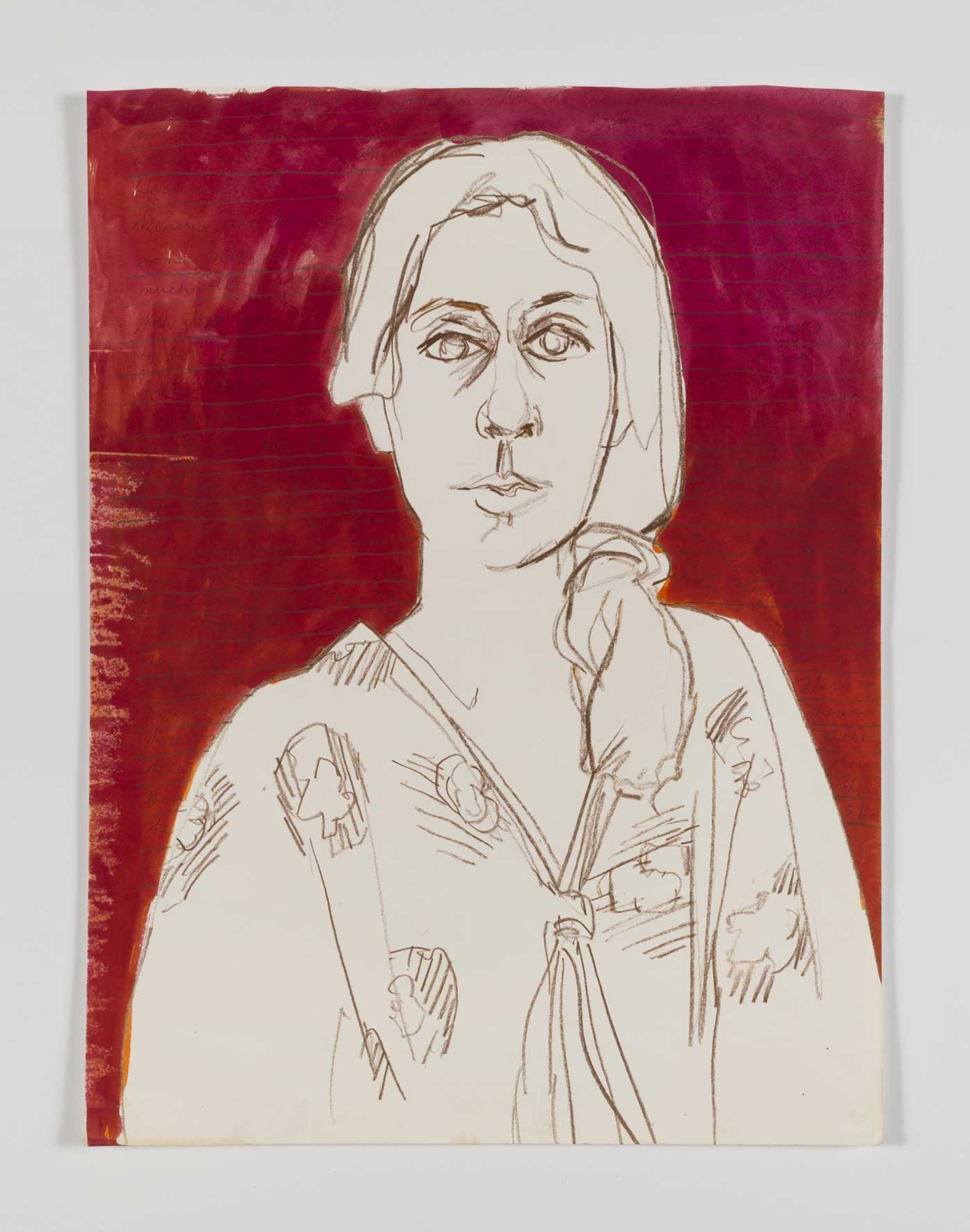

Luchita Hurtado. Untitled c. 1970s Crayon, graphite, and ink on paper. One of the images on show at Hauser & Wirth New York 22nd Street from 10 September © Luchita Hurtado. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane

In 1944, Noguchi introduced her to the Surrealist and art theorist Wolfgang Paalen. Hurtado liked Paalen, a cultivated Austrian from a wealthy Viennese family, from the start. “He was very bright, and he had this passion for things ... which I shared. I had tremendous ... energy.” From 1942 to 1944, Paalen had edited a ground-breaking art magazine, Dyn, with contributions from his first wife and fellow Surrealist, Alice Rahon, and from Henry Moore, Jackson Pollock, Henry Miller and Anaïs Nin. In the final, November 1944, issue he published Motherwell's essay "The Place of the Spiritual in a World of Property" as "The Modern Painter's World". Motherwell in turn conceived a new series of books, the Problems of Contemporary Art, for the publishers Wittenborn & Schultz, which published Form and Sense — a collection of Paalen's essays from Dyn—to coincide with Paalen's one-man exhibition at Art of This Century, Peggy Guggenheim's gallery in New York City, in April-May 1945.

Paalen was a prolific essayist, poet and playwright, fluent in English, as well as an artist who, like Matta, had a deep influence on the artists who formed the New York School of Abstract Expressionists. Once, when Paalen and Hurtado were staying with Motherwell and his actress first wife, Maria Emilia Ferreira y Moyeros, at East Hampton, Long Island, they gave the first public reading of Paalen's play The Beam of the Balance. Hurtado recalled 50 years later that when they read a scene "with the baroness shooting her husband in the middle of the ocean", Motherwell "had to stop reading because he thought it was so funny. He kept screaming with laughter. It was hilarious".

Paalen invited Hurtado to Mexico, where they travelled to the Gulf coast at Veracruz to examine the giant 3,000-year-old basalt Olmec heads in the jungle at San Lorenzo Tenochtitlán. The photographs that Hurtado took on that expedition appeared with Paalen's influential article on the heads in Cahiers d'Art in 1952. They married in 1947 and settled at Villa Obregon in the San Angel district of Mexico City. Paalen had a spectacular studio—where Hurtado also painted—and devoted at least half his energies to assembling a large collection of pre-Columbian art. They were neighbours of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera, and intimate with a clutch of British Surrealists: Edward James, Leonora Carrington and Gordon Onslow Ford—a friend of Paalen’s from the André Breton circle in Paris—and his wife, the Californian writer Jacqueline Johnson, who co-edited the final issue of Dyn with Paalen.

The studio at Villa Obregon, San Angel, 1946, with Paalen's painting Les Cosmogones Paalen Archiv, Succession Wolfgang Paalen Berlin

In 1948, Hurtado’s younger son, Pablo del Solar, died of polio, at the age of five. After this devastating loss, Hurtado, always sensitive to magic, omens and the extrasensory, felt haunted by Mexico, its soil and the Aztec goddess of the earth with "a death's skull, eagle claws, and a skirt of rattlesnakes. You feel this in the earth." Onslow Ford and Johnson had moved to San Francisco in 1947. Peggy Guggenheim had offered Paalen's 1945 Art of This Century show to Grace Morley, the inspirational director of the San Francisco Museum of Art. While that show did not transfer to San Francisco, Paalen was in contact with Morley in 1947 about a one-man show that took place at the museum in 1948. Encouraged by Onslow Ford and Johnson, and looking for a change from Mexico following Pablo's death, Hurtado and Paalen moved to the city in 1949.

Surrealism for the New World

At about the time that Hurtado and Paalen settled in San Francisco, Onslow Ford had been organising his own first show at the San Francisco Museum of Art. On a visit to the letterpress printer Jack Stauffacher, who was producing the exhibition catalogue, Onslow Ford admired a painting on the wall. It was by Lee Mullican, an artist from Chickasha, Oklahoma, who had served in the US Army with Stauffacher during the Second World War. So that, for one of Paalen and Hurtado's first evenings in San Francisco, Onslow Ford and Johnson took them to an evening of art films at the apartment shared by Mullican, Stauffacher and his brother, Frank, an avant-garde film-maker.

Mullican had discovered Dyn in the library of the Honolulu Academy while with the army in Hawaii, and had come to share Paalen's passion for the Indigenous art of the Pacific Northwest. Interviewed in 1992 and 1993 for Archives of American Art, Mullican summed up the revelatory mix of innovation and synthesis offered by Dyn at the time that Hurtado came into Paalen's world. "This was different than straight surrealism. This was different than cubism, which had always before been my big thing," Mullican said. "Here was a magazine being published with articles and reproductions about things I was not aware of ... I became really interested in primitive art, folk art, pre-Columbian art, Northwest Coast art ... there was a direct link between that and modern painting, for me."

We saw a school of whales. This was magic. And somehow I thought it was a very fine omen. I thought this is the place to be ... Nature is so important in California.Luchita Hurtado

Hurtado took to California from the first. One day Onslow Ford was showing them the coastline by Point Lobos, "when suddenly we saw a school of whales. This was magic. And somehow I thought it was a very fine omen. I thought this is the place to be ... Nature is so important in California." And she warmed to the artistic coterie in San Francisco. Besides Onslow Ford, Johnson, Mullican and the Stauffacher brothers, there was Morley; the architectural critic and film-maker Sybil Moholy-Nagy, a living symbol of Bauhaus; the poet and film-maker James Broughton; and the Greek poet and collagist Jean Varda, a close friend from Paalen's years of artistic discovery in France. Hurtado recounted how the two men had met: Paalen was on a beach in the South of France in the 1930s, and was writing lines by Sappho, in Greek, in the sand with a stick. "And along came Varda and saw this and was delighted and took up another stick and finished it. And they were friends from then on." Man Ray, then based in Los Angeles, photographer Hurtado at this time, reputedly asking her if she would pose naked with his wife, Juliet Browner.

Paalen and Hurtado bought a large, haunted Victorian house in Mill Valley, northwest of the city, near Sausalito. It was on a sloping, wooded site with a stream running through it, set amid giant redwoods that smelled of strawberries in the heat of the day, and shaded the afternoon sun. Paalen travelled to and from Mexico, eventually filling the Mill Valley house with pieces of Pre-Columbian art from his collection. To help make ends meet, they rented a room on the top floor to Mullican. For Mullican, Paalen seemed distracted, his mind still centred in Mexico, and focused on alterations to the house—removing stained glass windows—and on his essays, his artistic statements to the world, producing only a few small paintings in a small studio. Hurtado meanwhile painted in the dining room—using water colour, ink and crayon, where she had used oils in Mexico.

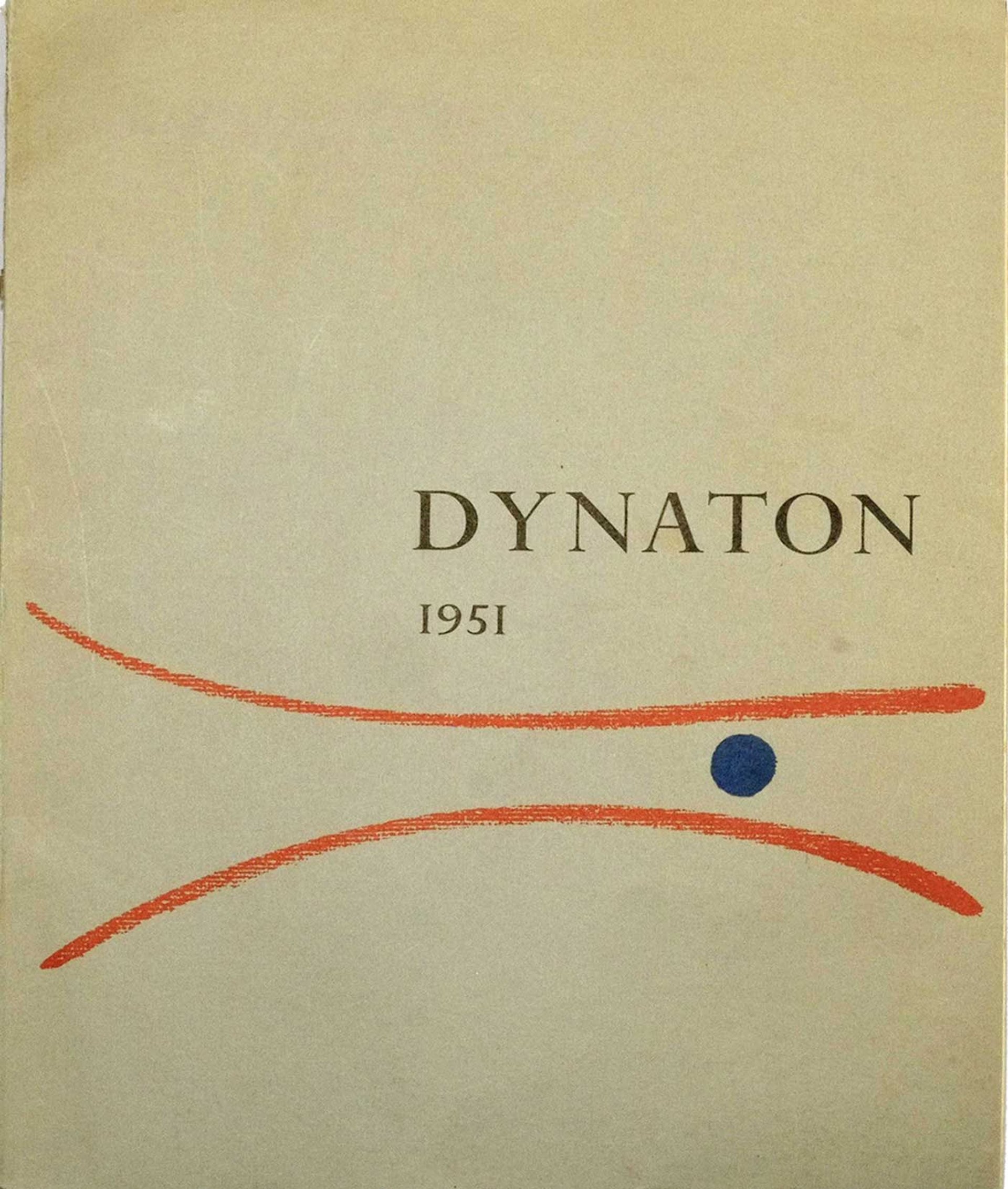

Cover of the catalogue for Dynaton, 1951, at the San Francisco Museum of Art, featuring the work of Gordon Onslow Ford and of two of Hurtado's husbands, Wolfgang Paalen and Lee Mullican

Mullican held a one-man show at the museum in July 1949. And then, with two years of preparation, the three men put on a ground-breaking group show, New Vision: Wolfgang Paalen, Lee Mullican, Gordon Onslow Ford and a catalogue (with essays by Paalen and Johnson) titled Dynaton, 1951—focused on their concerns with automatism, mysticism and Indigenous art. As Mullican recalled, "there was something in that Dynaton period that we all recognised and that held us together, and that we wanted to make this statement ... Paalen just said one day ... 'The time has come. We've got to do something.' "

The Dynaton show has come to be seen—with its emphasis on unleashing the power of the unimagined and the possible, and of treating paintings as "objects for meditation"—as one of the many parents of San Francisco's Beat Generation, hippie culture and the summer of love. One critic dubbed it “Surrealism for the New World”.

Los Angeles life

In the catalogue there is a Dynaton group photograph: reflected in a mirror, the ghostly image disrupted by long, dangling straws, with paintings hanging on the wall behind. Onslow Ford stands, smiling, relaxed, to one side; the immensely tall Mullican is at the centre, almost retiring into the shadows; Johnson leans in alertly from the right; while Hurtado and Paalen sit in front, together, on an upright, antique, sofa. Paalen leans forward, one elbow on each knee; Hurtado is poised, legs crossed, her feet elegantly shod, her hair pulled back, her right arm draped on the sofa as she looks, with serious gaze, to one side of the mirror's reflection. "Jacqueline [Johnson] used to giggle," Hurtado remembered, "and say, 'They're not real, those people. They're spirits. They're ghosts.' We all look like ghosts in the picture."

By the time Dynaton opened, the Mill Valley days were numbered. Hurtado wanted more children. Paalen, who was plagued by nervous and depressive episodes, and haunted by his family's history of mental illness, did not. They divorced. He left for Paris, and ultimately remarried and returned to Mexico. Hurtado and Mullican moved to Santa Fe and then to Los Angeles, where her son with Mullican, Matthew, was born in September 1951. The mores of the day meant that Hurtado and Mullican did not marry or live together officially until later in the 1950s. They had a second son, John, in 1962, and lived for the rest of their lives in a house in Santa Monica Canyon that Hurtado had found in 1951. They built a second home, at Taos, New Mexico—an adobe structure consisting of two large rooms—in 1972.

“I’ve always followed my needs, my heart, my brain”: Hurtado, in her Santa Monica home and studio © Oresti Tsonopoulos, Courtesy Hauser & Wirth

The Dynaton group may have been together for just two years, but Hurtado and Mullican remained on good terms with Paalen, corresponding with him and seeing him in Los Angeles, when he asked them to come to Mexico to work with him once more. He died by his own hand in 1959, while staying at a hotel in Mexico where he went while suffering depressive episodes. Two or three times a year, Hurtado and Mullican would visit Onslow Ford and Johnson, who had bought land at Inverness on the coast north of San Francisco, near Point Reyes, while keeping, at Sausalito, an old paddle-steamer ferry boat, the Vallejo, which they had bought with Varda in 1949. Onslow Ford and Varda had studios on the Vallejo, where Alan Watts, the influential broadcaster and writer on Zen Buddhism, later also lived. Through these visits, Hurtado and Mullican kept in touch with Varda, Watts, Broughton and other luminaries of the Sausalito and Bay Area crowds—which included the activist writers Lawrence Ferlinghetti, co-founder of City Lights bookshop; the poet Kenneth Rexroth; and Henry Miller, author of Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn—who played roles first in the San Francisco Renaissance, and then the Beat and hippie movements. Varda and Watts gave famous parties on the Vallejo, attended by Onslow Ford, Johnson, Mullican, Hurtado, Jack Kerouac, Allan Ginsberg and Maya Angelou—who lived in Sausalito while working as a professional dancer in San Francisco in the years immediately before she moved to New York in 1959 to focus on her writing.

In Los Angeles in the early 1950s, Hurtado and Mullican fell happily into a world of writers, film-makers and fellow artists. The author Christopher Isherwood and his partner, the portrait painter Don Bachardy, were their neighbours in Santa Monica Canyon. The ultra-Bohemian British poet and actress Iris Tree, mother of the screenwriter Ivan Moffat, lived above the merry-go-round at Santa Monica Pier. The novelist and screenwriter James Agee—who had recently completed work on the screenplays for African Queen and The Night of the Hunter—and his third wife, Mia Frisch, visited regularly, with Agee always happy to stay up all night talking and drinking. Their circle also included the designers Ray and Charles Eames; the film director Jean Renoir; Charlie Chaplin; and the artist Mary Wescher, widow of the Oscar-winning film composer Herbert Stothart, and wife of Paul Wescher, first director of the J Paul Getty Collection.

Mary Wescher introduced Hurtado and Mullican to the newly established Los Angeles gallerist Paul Kantor, who exhibited their work in 1953 and 1954. Hurtado made ends meet by working for the British costume designer and couturier Matilda Etches, who was much admired by her former collaborator Cecil Beaton. She also got into movies, playing a court lady in The Egyptian (1954), a film directed by Michael Curtiz—also director of Casablanca (1942), Mildred Pierce (1945) and White Christmas (1954)—with a cast including Michael Wilding, Jean Simmons and Peter Ustinov. "You have a face that is 100BC to 100AD,” Curtiz told her. “You are in."

I admired Lee [Mullican]’s work so much that all my energy went towards his work … and it was very difficult for me to accept that I, too, was workingLuchita Hurtado

In 1959, Mullican received a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, which he, Luchita and Matt spent in Rome, where Mullican painted in a studio near the Campo dei Fiori, and they entertained Isamu Noguchi, Peggy Guggenheim, and Willem De Kooning, who, like Mullican, and no doubt coincidentally, was engaged that Roman winter on black and white studies on paper. They then drove from Rome through Europe and back, camping at ancient sites, from caves of Altamira, to Lascaux to Brittany. After spending the winter in New York state, renting a house at Croton, near their old friend Ailes Gilmour—now married to the museum curator Herbert Spinden—they went home to California. Mullican took up teaching posts first at the University of Southern California (USC) and then, from 1962 to 1990, at the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), where, in 1965, his friend Richard Diebenkorn was briefly his colleague.

Hurtado, Mullican and their sons Matt and John were back on their travels in 1967 when they spent a year in Santiago, Chile—visiting Hurtado’s sister in Venezuela on the way—on an exchange between UCLA and the University of Chile, sponsored by the Ford Foundation. In 1980 they were in India, in Ahmedabad, to stay with Hurtado’s friend the art collector and industrialist Gautam Sarabhai, who had expanded his textile-focused family business into multiple industrial concerns. Sarabhai had been instrumental in setting up in 1961, with the advice of Ray and Charles Eames, the National Institute of Design—to improve industrial design in India—with its main campus in Ahmedabad. Their second visit to India in 1982 was followed by UCLA asking Mullican to set up exchange exhibitions—a show of US modern art (curated by Mullican) to go to India; and a show of Indian modern art to come to UCLA.

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled, c1990s. Graphite, ink, and collage on paper © Luchita Hurtado. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane

An ‘I Am’ awakening

Hurtado never didn’t paint, as she put it, and Mullican was always very encouraging. But—as she had during her marriage to Paalen—she put her children, her husband and his art first, often starting her own painting at 11pm, once everyone was in bed, and giving the kitchen table a thorough cleaning before she took up her brushes. Because of this, she said in a 2012 interview, she became “uptight” about promoting her own work, symbolically turning her canvases to the wall. “I admired Lee’s work so much that all my energy went towards his work … and it was very difficult for me to accept that I, too, was working.” It was not until she joined a women's circle in Los Angeles in 1971 that her attitude changed. The artist June Kozloff invited a large group of women artists to her house, where each was asked to announce her name and métier. Hurtado stated her married surname, and "artist". And, she remembered in 1995, the printmaker June Wayne called out from the other side of the room “ 'Luchita, what?!' And I said, 'I'm sorry ... June, Luchita Hurtado.' "

Hurtado took part in feminist group shows, including Invisible/Visible at the Long Beach Museum of Art in 1972, organised by the artists Judy Chicago and Dextra Frankel. In 1974 she held her first solo exhibition at the Woman's Building for feminist art in downtown Los Angeles, showing paintings that mixed English and Spanish words. In 1995 she looked back to the genesis of her I Am self-portraits from this period: "At a certain point, I said ‘there is no way that I can express, let's say, except by painting myself.’ I said, ‘This is a landscape, this is the world, this is all you have, this is your home, this is where you live.’ You are what you feel, what you hear, what you know."

While Surrealism had always been "there" in Hurtado’s work and she admired the Surrealists for their intellectual rigour—especially Paalen’s old sparring partner André Breton—and had strong feeling for symbols, she felt she was one of those artists whose work—like that of her friend Frida Kahlo— was essentially about her life. She never felt competitive with her artist husbands, but it was important that they have an aesthetic bond. When they were furnishing their Rome apartment in 1959, she and Mullican went regularaly to the flea market, "I would get something that he had seen and considered and wanted, or the other way round. I saw something and he would buy it." She could never have lived she said, laughing, "with a bad artist".

Summers were spent at the house in Taos. She found life in New Mexico an elemental, aesthetic and a sensory experience: "The sky, oh, the sky, and then the sounds, the crickets and you can see the walking rain. And the smells, you can smell the rain before it rains. And the fall, I think it's the most beautiful time of year, the fall when the air turns a violet colour."

I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn

Lee Mullican’s death in 1998 was like “losing a limb”, Hurtado said. She lost the peace of mind that she needed for painting. John Mullican had started work on a documentary, Finding Lee Mullican, before his father’s death, and completed it seven years later, after Lee’s retrospective, An Abundant Harvest of Sun, had been held at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) in 2005. Hurtado’s eldest son, Daniel del Solar, a broadcaster and media activist, died in 2012.

John Mullican and his brother, Matt, who had made his own name as an artist in New York and Berlin, felt their father still lacked recognition beyond Los Angeles. In 2014, John focused anew on family legacy, devoting himself to organising his father’s estate and bringing his parents’ works from locations in Los Angeles and New Mexico into one place, with the help of a studio director, Ryan Good, and a registrar. After two years of organising both parents' art, of discovering what they had to hand, the Mullican brothers realised for the first time the abundance and character of their mother’s work. Hurtado herself was amazed at what had survived. "With my mother still alive," John Mullican said last year, "I was determined to do something with it".

After 18 months’ work, Good organised an exhibition of Hurtado’s pictures at Park View Gallery in Los Angeles in 2016; the group show Made in LA was held in 2018 at the Hammer; there followed an introduction to Hans Ulrich Obrist, director of the Serpentine Gallery in London, and plans were made for her one-woman show there, I Live I Die I Will Be Reborn, encompassing more than 100 works. “My mother is an emerging artist at 98,” John Mullican said last year. “We are enjoying the ride … She is painting, she is creating. There is light on her… It’s thrilling to go into her studio and see her work. It is completely different from her earlier work.”

The Serpentine show transferred to Lacma on 16 February, but the the Covid-19 pandemic caused it to be temporarily closed and led to the cancellation of a planned transfer to the Museo Tamayo Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City—founded by Hurtado's old friend Rufino Tamayo, her first artistic mentor nearly 80 years ago. In the early weeks of the lockdown, Hurtado was pictured on social media at her house in Santa Monica, painting on a balcony, her gaze turned, as ever, on nature. An exhibition of her work at Hauser & Wirth, in Zurich, Just Down the Street, reopened on 11 May and ran until 31 July. Another show, Luchita Hurtado. Together Forever—including over thirty works from the 1960s to the present day—opens at Hauser & Wirth New York 22nd Street, on 10 September. Seventy-five years after Paalen’s 1945 show at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century gallery on 57th Street—on the eve of the first of Hurtado’s artistic and personal migrations—her own work is being recognised (after a debut show last year) in the city of her upbringing, the city where her artistic journey began.

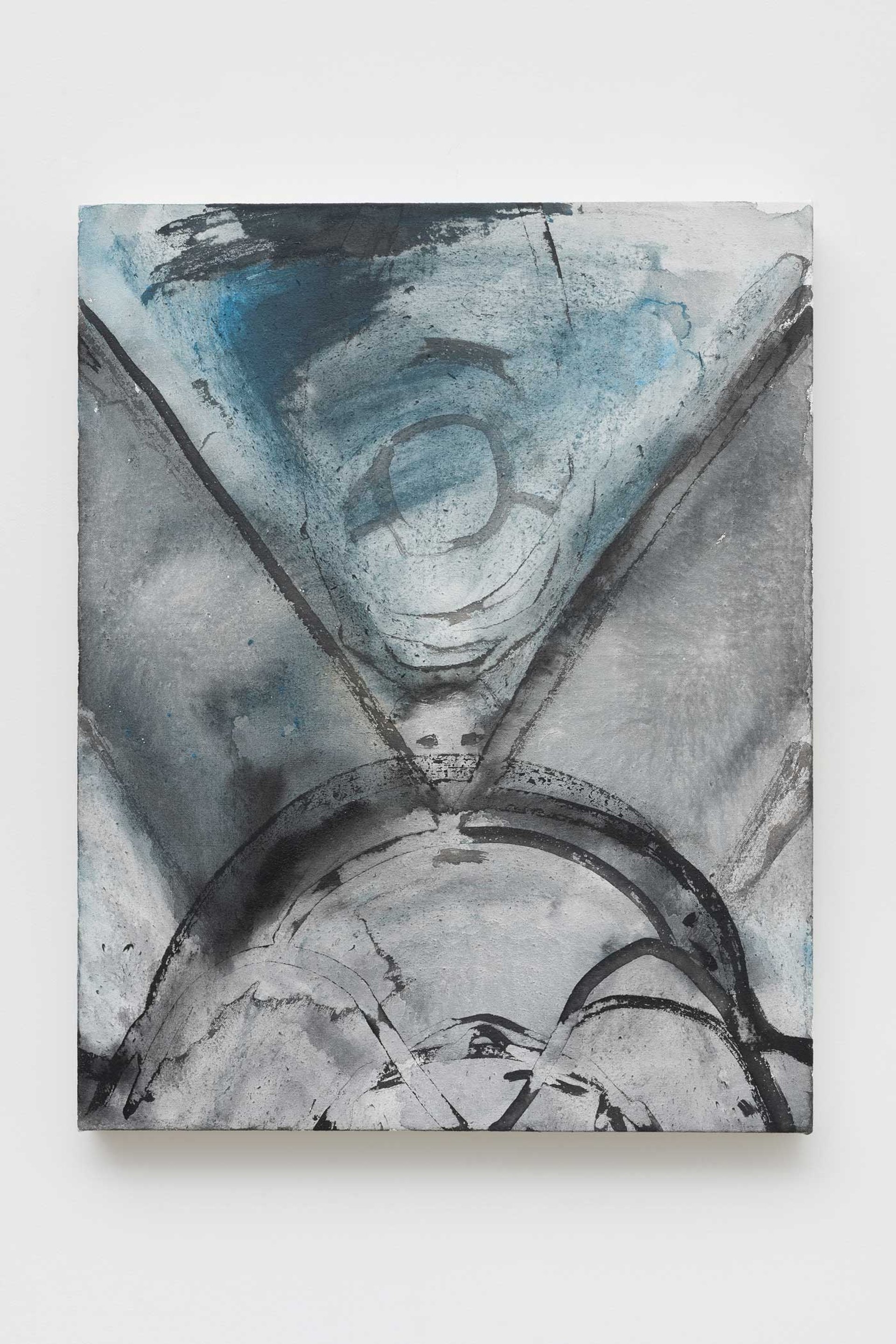

Luchita Hurtado, Untitled (Birthing Mother Earth) 2018. Acrylic and ink on linen © Luchita Hurtado. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jeff McLane

In a video made for the Serpentine show, Luchita Hurtado paints a “birthing” picture—“motherhood is full of wonderful times”—boldly and quickly. “That’s done!” she concludes. The final scene in the video shows this earth mother of art basking in the sun, grasping the branches of a reclining tree and smiling her huge, candid, smile: “It’s just the joy of life."

• Luchita Hurtado, born 28 November 1920, died 13 August 2020