In a piece of Covid-induced coincidence, 2022 is turning into quite a year for Louise Bourgeois, the French-born, New York-based artist who lived to be nearly 100 and died just over ten years ago. While an exhibition at London’s Hayward Gallery, dedicated to the fabric works made in the last two decades of her life, opened to a series of ecstatic reviews last week, another focussing exclusively on her paintings comes to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York on 12 April. Shoe-horned between these is another ambitious offering at the Kunstmuseum in Basel opening this weekend, in which the US artist Jenny Holzer has cherry-picked work from across the immense Bourgeois archive to create a unique interpretation of her work.

Holzer, known for her campaigning use of text and for frequently presenting work in public spaces—including fly posters, advertising screens and most recently on the sides of trucks—has perhaps unsurprisingly chosen to look at Bourgeois’s own writings and graphic use of words. The pair knew each other, and Holzer says that her objective throughout the project’s three-year gestation has been to illuminate “the quantity and quality, tenderness restlessness and sheer murderousness” in Bourgeois’s vast output.

There are more than 250 works across nine galleries in the museum’s most recently completed building, the Neubau, and Holzer, as one artist appraising another, has been able to take more liberties than the average curator. “I like installation art,” Holzer tells The Art Newspaper. “And I wanted parts of the show to be like a formalised version of visiting her house, where she was surrounded by fabrics and objects and artworks in progress.”

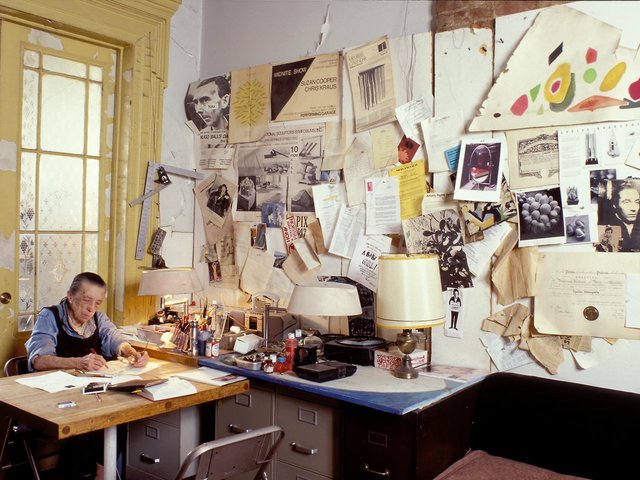

Jenny Holzer photographed in the exhibition Louise Bourgeois x Jenny Holzer at the Kunstmuseum Basel Photo: © Xandra M. Linsin

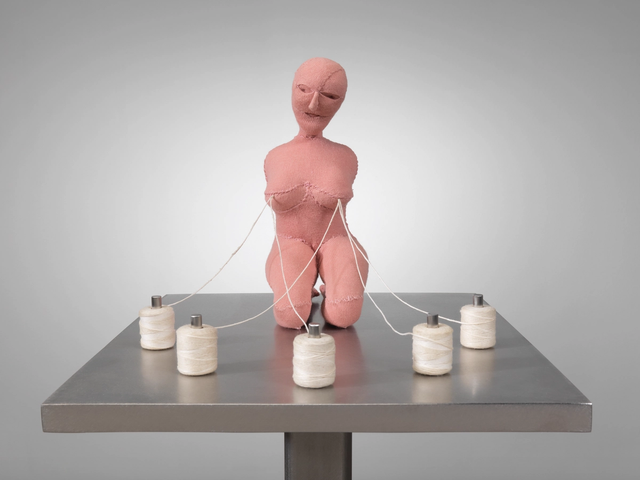

While certain galleries provide calm intervals, others clearly express Holzer’s vision. In one an entire wall is papered in (perfectly executed) facsimiles of loose-leaf pages covered in Bourgeois’s beautiful handwriting. These are her obsessive responses to the psychoanalysis that she began in 1951 following her father’s death. Another gallery has small framed drawings and fabric works arranged in the shape of an eye: both a comment on Bourgeois’s interest in the sexual importance of the gaze, and an acknowledgment of possible Surrealist influences in her work. The final room is an overwhelming explosion of blood red in swirling concentric gouache-painted circles, and raw depictions of childbirth and female organs. In between, a work by Bourgeois from Holzer’s own collection, of swollen male genitalia drawn on the back of a White House envelope, has pride of place, demonstrating Bourgeois’s dry dirty wit.

It is also apparent that Holzer has not held back on her love of tech. One of the French artist’s major installations, The Destruction of the Father, a diorama of outsized latex abscesses doused in glowing red light, has been given the AR treatment. Visitors can use their phones to witness its deconstruction to a soundtrack of Bourgeois singing a children’s nursery rhyme. Holzer’s aim is to bring new audiences to the work.

The Destruction of the Father (1974-2017) by Louise Bourgeois Photo: Johee Kim

An enormous accompanying book, called The Violence of Writing Across a Page and a work of art in its own right, has allowed Holzer to create dialogues between Bourgeois’s work and those from the museum’s historical collections. It offers a chance to read some of the artist’s texts more closely and reveals Holzer to be as fascinated by sex and death as Bourgeois herself.

Also, four works by Bourgeois have been placed by Holzer in the Old Masters galleries of the original Kunstmuseum next door. In a juxtaposition of Cumul 1 (1969), an unctuous sculpture of white marble protrusions, with a 16th-century portrayal of Thisbe poised to murder Pyramus by Niklaus Manuel, the 20th-century artist more than holds her own in both presence and nerve.

• Louise Bourgeois x Jenny Holzer, Kunstmuseum Basel, 19 February-15 May