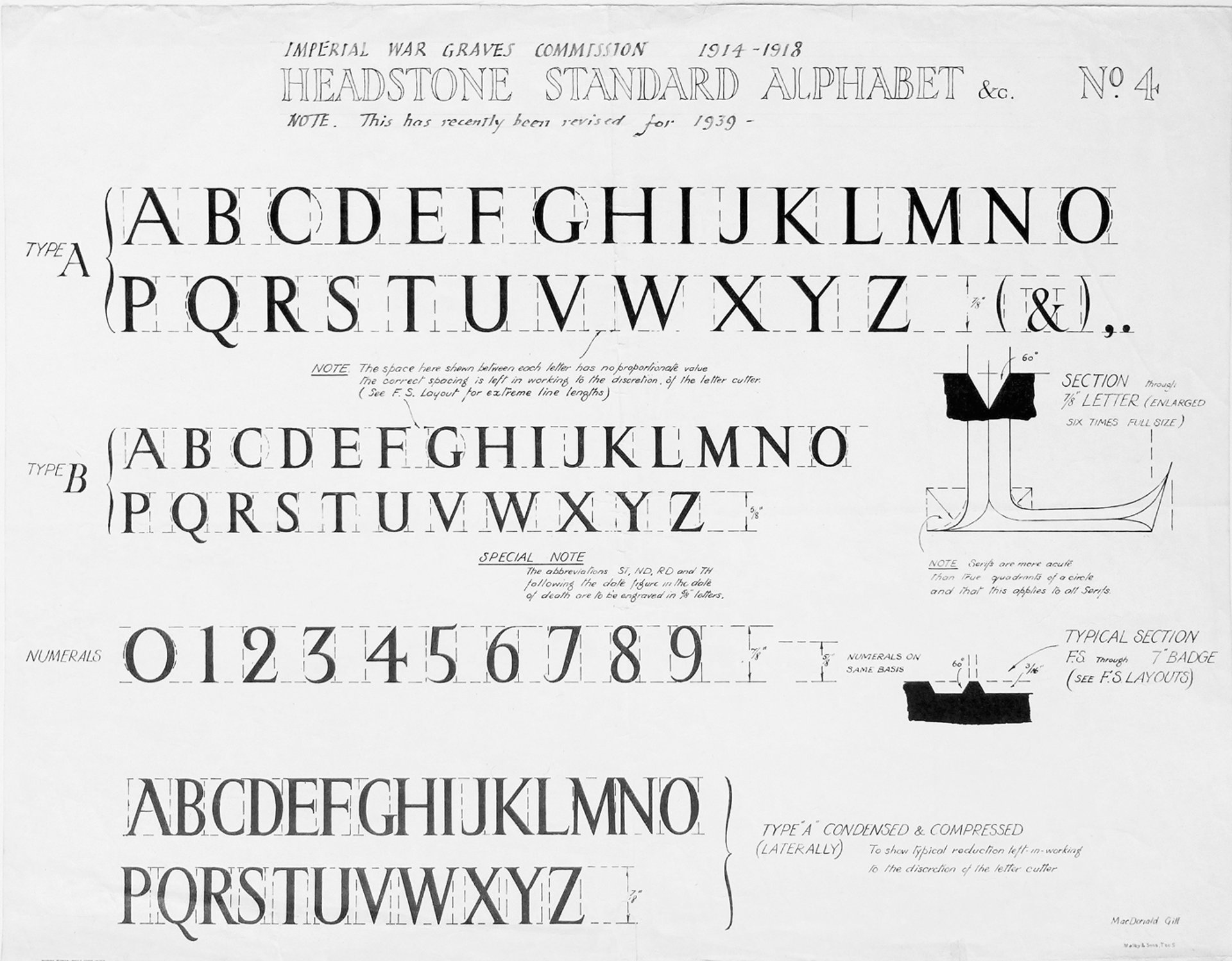

In January 1918, while still in his early 30s, MacDonald "Max" Gill was chosen to design the alphabet used on the headstones and memorials of the Imperial War Graves Commission (IWGC), intended to give each of the British and Empire fallen of the First World War a uniform gravestone or (if their bodies were never recovered) a uniform inscription on a collective memorial to the missing. The work of the IWGC—now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC)—arguably adds up to the largest single, cumulative artwork of the 20th century, memorialising, in 23,000 locations in more than 150 countries, the 1.7 million British and Commonwealth citizens who died in action in the First and Second World Wars. Its tone was set by Max Gill’s chaste Roman lettering—a style he modified and made bolder in 1940 for the graves of the Second World War.

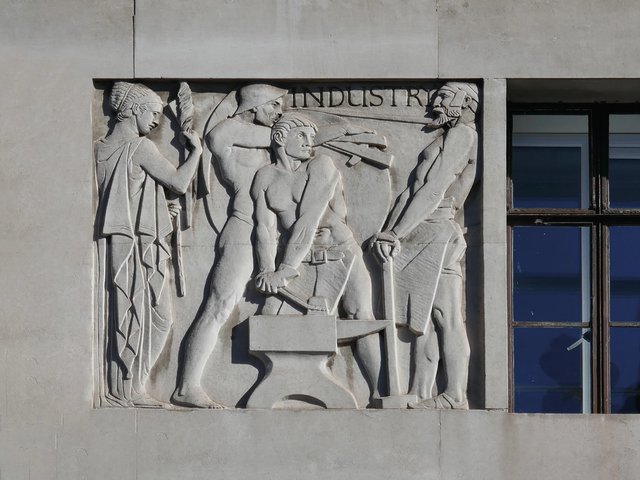

Both Max and his elder brother Eric studied lettering with the great calligrapher Edward Johnston, creator of the London Underground typeface. Some later commentators—unaware of Max’s achievements—have gone as far as to wonder if the war graves commission might have accidentally gone to the “wrong” Gill. The brilliant, but controversial, Eric was an able self-publicist who had already made his name as a letterer and sculptor, winning a commission to carve the Stations of the Cross for Westminster Cathedral (produced between 1914 and 1918).

But there had been no mistake. Sir Frederic Kenyon, director of the British Museum and chairman of the commission, believed “no better authority could be desired than Mr MacDonald Gill”. The influential architectural writer Lawrence Weaver ranked the two brothers as equal in their work as designers of lettering. Max Gill had made a name of his own in the early 1910s when he collaborated regularly with the architect Edwin Lutyens who went on to became the dominant creative agent in the work of the War Graves Commission and, presumably, the figure who secured Max Gill’s appointment to the commission as the adviser on lettering.

The alphabet created by Max Gill for the Imperial War Graves Commission in 1918

Eric Gill was a genius with a chisel and went on to design the ubiquitous Gill Sans for Monotype. He was clearly put out by being, for once, outshone by the less showy younger brother with whom he had lived, studied and collaborated. The brothers argued “not very amicably” early in January 1919. In the same month, Eric pitched (unsuccessfully) for work training masons to cut the lettering for the War Graves headstones, and he subsequently published an embarrassing polemic in the Burlington Magazine criticising the consciously uniform nature of the project and Max’s lettering. The preference for uniformity had, however, a moral dimension; it was about recognising the equality of those serving in their sacrifice and death. Max Gill not only designed the lettering, he produced elegantly simplified drawings of the regimental badges which could be carved directly into the Portland stone.

Tyne Cot war memorial, near Passchendaele, Belgium, demonstrating the egalitarian uniformity of the Imperial War Graves Commission headstones Gary Blakeley / Wikimedia Creative Commons

This extraordinary work is an important aspect of Max Gill’s career, which is explored in a scholarly new biography, MacDonald Gill: Charting a Life, by Caroline Walker—Max Gill’s great-niece. Max Gill was a man of many talents: architect, letterer, draughtsman and mural-painter, and he was also a standout mapmaker-artist. In all these fields, his work was rooted in the high-minded Arts and Crafts tradition that strove to make the simple and ordinary both beautiful and useful.

Max and Eric were two of the 13 children of Arthur Tidman Gill, a clergyman. Max was born in Brighton in 1884 and grew up in Bognor Regis—and reminders of this seaside-town boy echo throughout Walker’s enjoyable biography. Max Gill’s work also provides a narrative of changing British cultural identity during the first half of the twentieth century, with Max entering manhood in an age of innocent Edwardian revelry before Britain was catapulted into the tragedies of the First World War, then taking the role of bystander during the long retreat of empire, and finally, as an older man, watching troops returning to battle to fight in the Second World War.

A secular painted ceiling: Detail from Max Gill's map of Antarctica, showing Ernest Shackleton's ship Endurance trapped in the ice, at the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, 1934

Throughout it all, Max Gill worked on forward-thinking commissions linked to the new horizons opened up by technology and advanced modes of travel. He produced posters for steam mail-ship routes, for post-office wireless stations, for the electrically-powered London Underground, and drew maps for ocean liners. The need to earn a living from his art meant he kept working during the years of economic depression, producing posters, maps and monuments, even executing a secular painted ceiling in 1934 when he created maps of the Arctic and the Antarctic for Herbert Baker’s Scott Polar Institute in Cambridge.

Although Max Gill trained as an architect in the office of Nicholson & Corlette, he was an active member of the Art Workers’ Guild, and gained an early reputation for his highly original mapmaking. In 1909, Lutyens commissioned an overmantel wind-dial map for Nashdom, the house in Buckinghamshire he was building for the English-born Princess Dolgorouki. Lutyens then asked for wind-dial maps for Howth Castle, Co Dublin, and for his 1913 conversion of Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland. When he restored Lambay Castle, near Dublin, for Cecil Baring, it was Max Gill who designed the plaque commemorating the work.

Max Gill's wind dial created as part of Edwin Lutyens's alterations to Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland, 1913

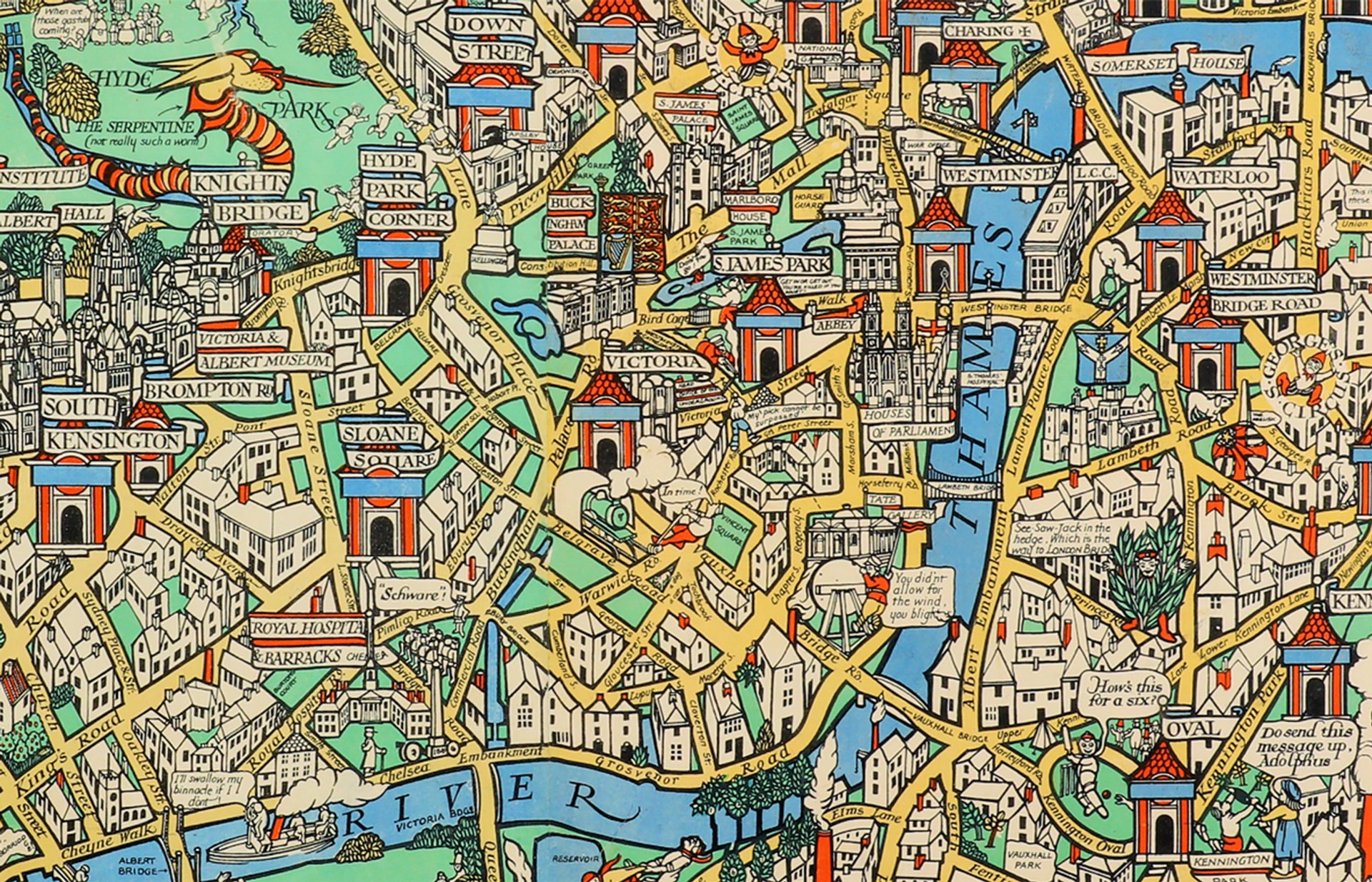

As Walker shows, it was but a short step from these wind-dials to Max’s famous 1914 Quad-Royal size (101cm x 128 cm) Wonderground Map of London Town, a work that was an instant hit. Commissioned by Frank Pick, commercial manager of the Underground Electric Railways of London, his map celebrated the joys of travelling on the Underground. The Standard called it: "one of the most striking efforts in the way of pictorial burlesque ever attempted. . . Probably no other single sheet of the same size has ever before been so crowded with jokes, puns, and witticisms as this one is".

Pictorial burlesque: Detail from Max Gill's Wonderground map for London Transport, 1914

One of Gill’s major architectural projects was working with the leading Art Workers' Guild member Halsey Ricardo on Sir Ernest Debenham’s Bladen estate in Dorset. Here, between 1914 and 1919, he helped create a new progressive estate village, with cottages in traditional styles. Gill married Muriel Bennett in 1915 and started a family, and in 1919 he and his wife returned to his childhood haunt of Chichester where he continued his varied output as jobbing architect and artist. Max Gill was also a skillful decorative muralist and, in 1927, he painted a ceiling decoration on the subject of The Creation for the chancel for ES Prior’s St Andrew’s Church in Roker, Sunderland. Even surrounded by Arts and Crafts masterpieces by Prior, Ernest Gimson and Alfred Bucknall, this is an outstanding work.

Max Gill's ceiling decoration on the subject of The Creation for the chancel for E. S. Prior’s St Andrew’s Church in Roker, Sunderland, 1927

Gill went on to take on a lot of memorials and rolls of honour, and a number of church projects, although his best paid project of the 1920s was the public grandstand and new weighing-room for Goodwood racecourse in Sussex, for the 8th Duke of Richmond. He also designed and built a number of simple, often thatched, Arts and Crafts-inspired houses, as well as his own 1926 home at South Nore, West Wittering—although this was a white-painted house with a tiled roof and sea views. Towards the end of his life, he divorced Muriel and married his long-time companion and collaborator the much younger Priscilla Johnston, daughter of his friend and former teacher Edward Johnston.

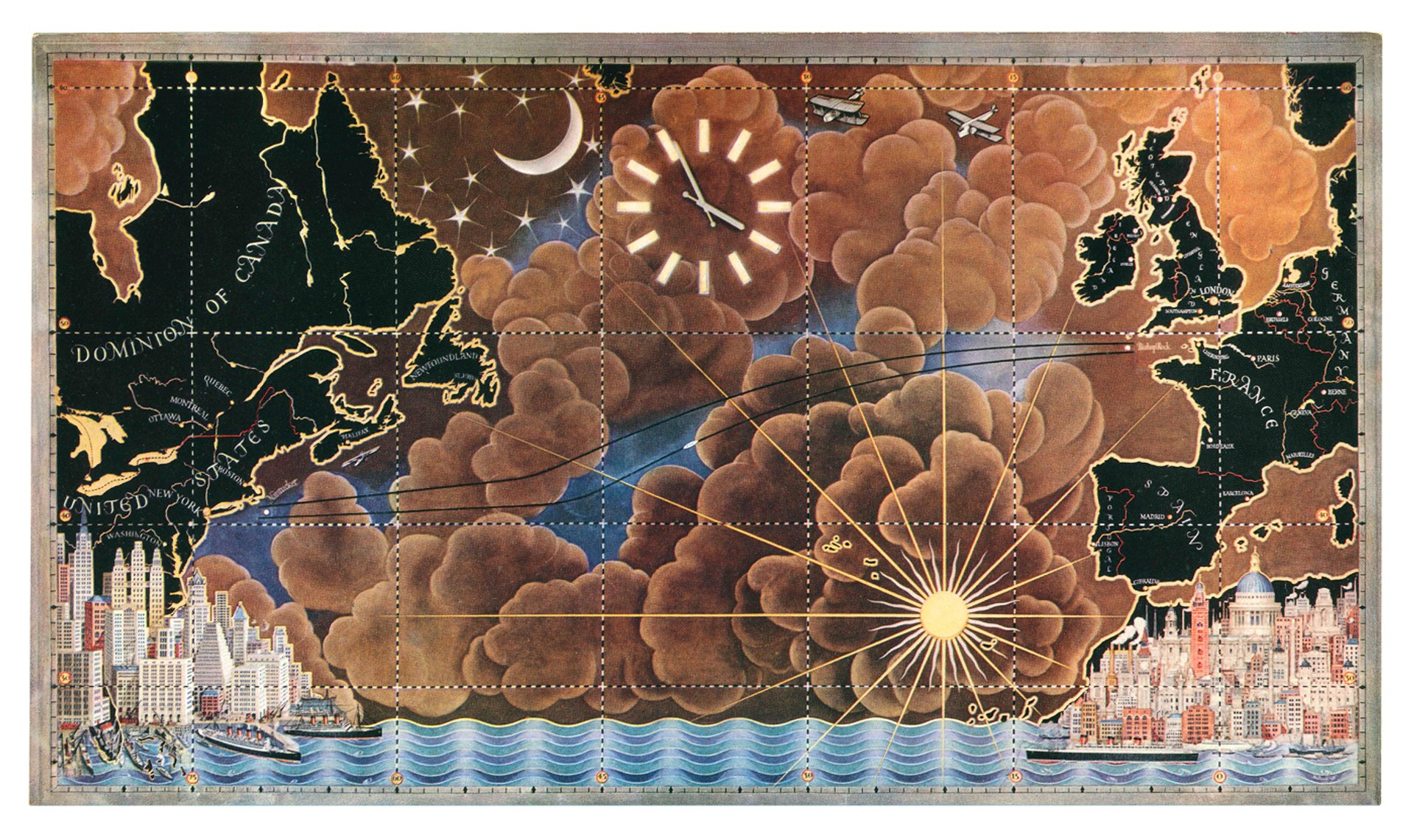

His graphic work was always in demand. In 1920, he provided one of the first diagrammatic plans for the London Underground system (now eclipsed by Harry Beck’s iconic 1931 design). Advertising was booming and he was commissioned in 1919 to create an early poster by Shell-Mex on the theme: Half-way round the World on “Shell”. He also produced work for the 1924 British Empire Exhibition in Wembley, and provided the cover for the souvenir volume, Pageant of British Empire, which promoted the economic possibilities of the Empire’s twilight years. Sir Leopold Amery, the chair of the Empire Marketing Board, commissioned one of Max Gill’s most famous works, Highways of Empire, in 1926. His almost Art Deco, large-scale mural of shipbuilding was installed in the UK Government Pavilion at the Glasgow Empire Exhibition in 1938, receiving special praise from The Manchester Guardian which reported: "The frescoes are the jam, jolly good jam too".

Max Gill's map of the North Atlantic, oil on panel, for the Cunard ocean liner Queen Mary, 1936 Caroline Walker

Beautifully illustrated and clearly written, Caroline Walker’s book is an engaging study of an artist who came to maturity at the end of the nineteenth century and whose work partook of generous-spirited artistic ideals, formed at a time of accelerating globalisation. Gill’s output was rooted in a deep love of the historic but it is also unmistakably of its time. He belongs to a rich chapter in the history of English art and design that is all too often overlooked in our enthusiasm for the rise of the adventurous but clinical modern, which (all too quickly) overtook it.

- Caroline Walker, MacDonald Gill: Charting a Life, Unicorn Publishing, £30 (hardback)