Bird’s-eye views of flooded cityscapes, once the province of science fiction and disaster movies, are now the stuff of news reports about extreme weather events made worse by human-caused global warming. In Adaptation (2019-22), a short film by Brooklyn-based artist Josh Kline making its debut at LAXART, flooded is Manhattan’s new normal. The film follows a group of divers going about their day exploring submerged skyscrapers, building on a project Kline began in 2019 to imagine a near-future world where we’ve adapted to live with disaster.

Your 2019 exhibition at 47 Canal, Climate Change: Part One, used sculptures and installations to envision a world of melting Antarctic ice, rising seas and dissolving structures befitting a disaster movie. How does Adaptation relate to those works?

Moving-image works were the catalyst for all of it—for my whole Climate Change project—and have been in the plans from the beginning. Loose ideas for the works at 47 Canal, my new film Adaptation and a larger unrealised installation about climate-driven migration have been accumulating in my computer since 2014. With projects like Climate Change, I produce a larger installation in parts, as exhibition opportunities and the space and financial support that comes along with them appear. Eventually, if the stars, curators and galleries align, I can put some or all of the pieces together.

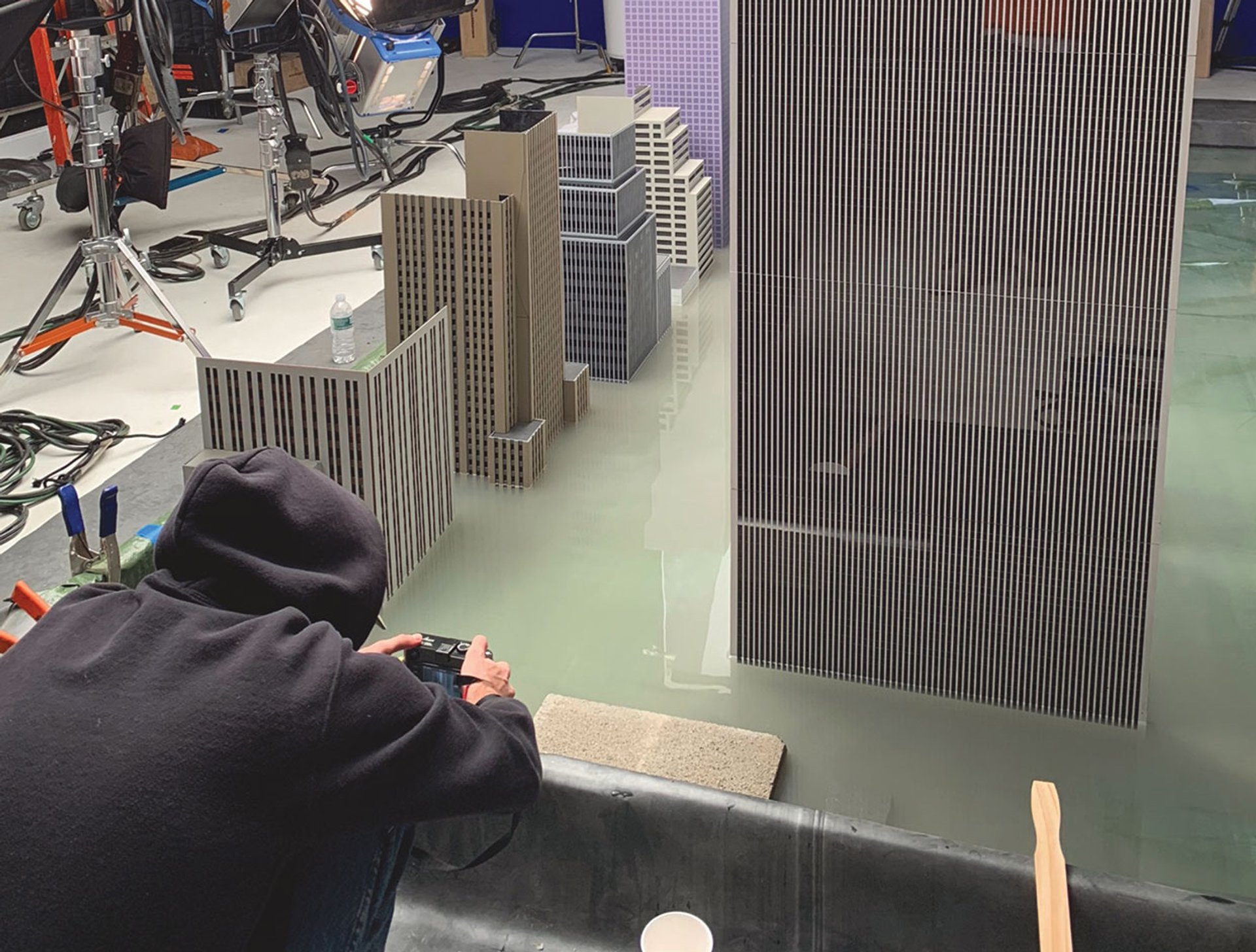

You opted to use largely analogue techniques to create the drowned New York of Adaptation; what attracted you to this earlier era of cinematic special effects?

The video art of the last decade—including much of my own work—has been defined by slick high-definition video, hyper-realistic CGI animation, and graphics inspired by and critiquing (or glamourising) commercial imagery. This style of video art is everywhere now. It looks like 2013. Film as a medium, because of its long use in cinema—and in sci-fi movies—is largely free of those associations. It isn’t specifically tied to our own time. There’s also an element of deep nostalgia that comes with film that I want to tap into and work with—to provoke a nostalgia for the present and explore its loss in the face of what’s coming.

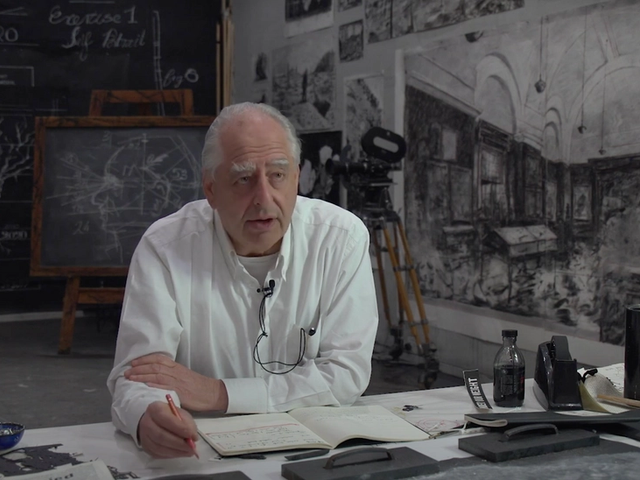

I’ve always loved Alien and the original Blade Runner, movies that use earlier, more handmade special effects—practical scale models, matte paintings and blue screens. Also sci-fi made on the cheap in the 1970s by the BBC for television. This method of working is grounded in the fabrication of physical objects and has a tangible connection to sculpture, but is also free of the many associations that contemporary tools of digital image manipulation are burdened with, especially their relationship to post-truth technologies and disinformation.

Behind the scenes during production of Adaptation in September 2019 Courtesy of LAXART

Cinematic depictions of global disaster tend to be fast-paced and chaotic, but your film has a very lived-in, even calm rhythm to it—as if living with cataclysm has become routine. Do you consider your film a projection of how things could be in the near future or an allegory of how they already are?

Both. It’s shocking how acclimated we’ve all become to thousands upon thousands of people dying every day from Covid-19. After the initial shock—however long that lasts—catastrophe just becomes the world you live in. That kinder, less lethal world before the shock starts to fade away. I’ve been in Brooklyn for almost the whole pandemic. During lockdown in March and April 2020, every five minutes sirens were screaming outside my window as ambulances rushed by in the empty streets. Meanwhile, inside my apartment I was spending my days endlessly washing dishes and wiping down groceries with isopropyl alcohol, all while wondering about the lives in those ambulances—and wondering if I would end up inside one of them because of my asthma.

From the moment we went into lockdown, the Covid-19 pandemic has felt like a dry run for what’s going to come when the climate crisis really kicks into high gear in the coming decades. It’s been almost two years since the pandemic erupted in the US and that “return to normal” is nowhere in sight. If we don’t take our economic, political, agricultural and biological systems in hand and make major course corrections, we’re going to give up more and more of that “normal” as the century goes on. Adaptation is an image of working people forced to adapt to that lack of “normal”. It’s an image of survival.

How will your Climate Change project grow and evolve from here?

I have ideas for videos that will be incorporated into that unrealised installation about migration and refugees. I’m planning to work on that in 2022 and 2023, hopefully shooting new videos in the summer and autumn. I’m also working on a screenplay for a feature-length film that was originally meant to be part of all this, but I’m not sure if it will be possible to make that in the art industry. It’s really becoming a movie. The feature is set in the same world as Adaptation, but it has much more of a plot—there’s a story and fleshed-out characters. It’s a full-on narrative. My biggest discovery during all this time stuck working in my kitchen during the pandemic has been that I’m capable of storytelling.

• Josh Kline: Adaptation, LAXART, West Hollywood, until 9 April